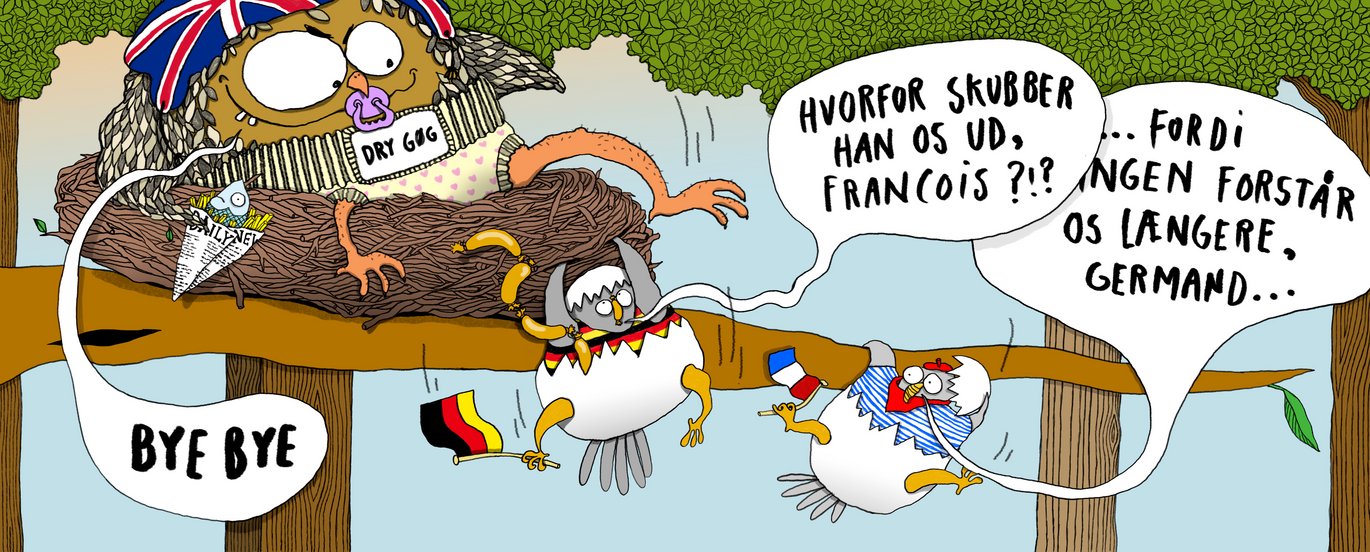

Foreign language programs in crisis: English is pushing French and German out of the nest

Admissions to German and French programs at AU have been declining for years. And in the most recent round of admissions, they reached a new low. The erosion of loss of foreign language skills in Denmark is a threat to culture, diplomacy and international trade. According to Arts dean Johnny Laursen, who describes the situation as “extremely urgent” the root of the problem is an educational system which devalues foreign languages. And the window of opportunity for doing something about the situation is closing fast, because the educational system changes course very slowly, and the results will take years to manifest themselves.

“It looks weak,” said Johnny Laursen, dean of the Faculty of Arts at Aarhus University

, leafing through a stack of large printouts. The printouts are records of the admissions stats for the faculty’s BA and MA foreign language programmes from 2016 to the present.

“Admissions to French are weak. It’s better for German, but still weak. There was a dip this year, but admissions have been weak throughout the entire period. And we need to factor in dropouts on top of that,” Laursen said.

At Aarhus University, the number of students offered admission to the BA program in German fell from 29 in 2019 to 23 in 2021; the number of students offered admission the BA in French fell from 18 to 11. The stats for the MA programs are even worse: in 2020, for example, the French program admitted five students and the German program admitted six. Since 2016, the German BA program has admitted between 32 and 23 students a year; the French BA has admitted between 21 and 11. This is far from enough, explained Johnny Laursen.

“Given the average dropout rate for a degree programme, we need to admit 35 students to have a normal class, with the personalities and friendships that exist in a group of peers,” the dean said.

Low admissions affect the learning environment negatively, which in turn increases the risk that students will drop out.

“Students are dependent on how well they get along with the other students. It’s something we’re concerned about. The students have good contact to the research groups and lecturers on their programs, but that’s not the same as having a group you can hang out and drink a beer with after class. This affects dropout rates. We know this,” said Laursen.

Johnny Laursen, dean of the Faculty of Arts. Photo: Lars Kruse, AU.

But weak admissions have consequences beyond the quality of the foreign languages learning environment at AU; these programmes themselves are part of a linguistic infrastructure which is crumbling away. With the exception of English, fewer primary and secondary students study foreign languages. As a result, fewer of them apply for admission to foreign language programmes at university, which in turn means that very few graduates are qualified to teach languages at primary and secondary school level.

“The food chain is broken, or at the very least stagnating. We view this as a fundamental problem,” Laursen said.

The National Centre for Foreign Languages

These problems aren’t new. In 2017, then Minister for Higher Education and Science Søren Pind unveiled a national foreign languages strategy intended to “improve the Danes’ foreign language skills”.

In practice, this meant that the government allocated 100 million kroner to the project, and that the National Centre for Foreign Languages (NCFF) was created about three years ago.

Hanne Wacher Kjærgaard, who is director of the NCFF’s western division, has an office on the fifth floor of one of the Nobel Park’s red-brick buildings. She explained that the NCFF was tasked with “ensuring that more students become more proficient in more languages in addition to English, and to work to ensure that the degree programmes are relevant and of high quality” over a five-year period.

Hanne Wacher Kjærgaard, director of NCFF (West). Press photo

On the way down the corridor to her office, I noticed the German newspaper Die Zeit on the counter in the kitchenette, and there were clippings from other foreign newspapers on her office door.

Behind this door, Hanne Kjærgaard leads the fight against the the decline of foreign language skills in Denmark. By way of introduction, she quickly sketched out the history of the erosion of foreign languages in the Danish educational system.

“In 2005, over 40% of graduates from upper secondary school could speak three languages. In 2016, the figure was just four percent, and last year just under two percent graduated with three languages,” Kjærgaard explained.

Just one in five municipal schools offered French in the 2019-2020 school year, she added. You can see where the schools that offer French are located on an interactive map of Denmark from folkeskolen.dk. They’re primarily centered around Copenhagen. French has become “a phenomenon of the capital and the metropoles,” she explained.

French is not offered at municipal schools in much of Jutland. To take French at a Danish municipal school, you need to live close to a larger city, preferably Copenhagen. Explore the interactive map here. Note that the map displays the number of municipal primary schools that offer French. It isn’t possible to see what percentage of a municipality’s schools offer French. The statistics on which the map is based are from NCFF. Map: Folkeskolen.dk

According to Kjærgaard, Denmark stands to miss out on a wealth of opportunities because so few pupils and students acquire foreign languages.

“We’ll miss out on political influence. After Brexit, it’s to be expected that French and German will play a greater role in the EU. We’ll also lose something when it comes to security policy. And we won’t have the necessary language competencies to be able to contribute to the NGOs, where English isn’t always the preferred language, and generally speaking, our understanding of the world will be impoverished,” Kjærgaard said.

And although many Europeans speak English, Kjærgaard contends that something will always be lost in translation: as non-native speakers, we encode English with our own cultural background, which always has an effect on communication; although we may believe that we all use and understand English words in the same way, in reality, the same English word can mean something different to a German and a Dane, she explained.

“Values are also coded into language, and language is always adapted by the context in which it exists. If we are forced to put all of our information eggs into an Anglo-Saxon basket, we also end up conveying the values that come with the basket itself,” she said, adding:

“If an American wants to explain something or other, he does so in relation to his own cultural background and knowledge. What this means is that it’s never neutral. This also happens when you use interpreters, because there are multiple cultures involved, not just multiple languages.”

The significance of cultures

One afternoon in August in a small classroom in Katrinebjerg, I met another AU researcher about this relationship between culture and language.

When I arrived, Steen Bille was standing in front of a blackboard and eleven students, teaching French. Bille has been affiliated with AU for the last nineteen years and was appointed professor of French at the School of Communication and Culture last October. There was a list of the world’s Francophone countries on the blackboard behind him.

The list was long: for better for for worse, France has been a major player in world history, including as a colonial power; that the French language is spoken all over the world is one legacy of this history. But French culture hasn’t only influenced the world through colonization. The country and its language have also played a decisive role in the history of democracy in the Western world.

“Without a doubt, it’s a country with an illustrious and proud cultural and intellectual history which has shaped our understanding of what democracy is. France contributed to the foundation of everything we understand by human rights, and just generally the conception of democracy as something that makes room for the cultivation of the individual, education, critical thinking and reflection,” Bille said.

Democracy is still a lively subject of debate in France, which has a unique culture of public debate. And to understand this extremely language-conscious culture, you need to understand the language in which it is articulated. If we can’t speak French, we cut ourselves off from the opportunity to gain important insights into European culture – and by the same token, into Danish culture, Bille believes.

“We miss out on some intellectual and human horizons that have to do with the diversity with regard to the diversity in how we think about culture that we have here in Europe. We miss out on this diversity, and just generally on the nuances that can help make Denmark a country where we have every opportunity to become cultivated and insightful,” he said.

What’s more, he explained, the small classes have consequences for the learning environment.

“We’re getting close to the pain threshold. When we get down to under 12 in a class, you start having a lot of empty chairs between you.

If there are only eight or nine students, it’s hard to divide them into groups, and you don’t have that productive dynamic of different ways of thinking. It’s important to have around twelve students, and preferably 25, of course. With fewer than twelve students it starts getting a little hard to handle.”

Steen Bille, professor of French Photo: AU

The low status of foreign language programs

According to NCFF’s Hanne Wacher Kjærgaard, there are two primary reasons for the crisis facing language programs. The first is a cuckoo in the nest: English has become a natural part of everyday life for many young people, who interact with people all over the world on YouTube, Facebook and other social media. As a result, there’s a widespread belief that you can easily get by with English, Kjærgaard explained.

“That narrative that everyone speaks English hasn’t benefited the other foreign language programs,” she said.

But even though English has pushed the other foreign languages out of the nest in Denmark, this doesn’t mean that people in other countries share the Danish preference for English.

“You don’t have to travel that deep into Europe before people either can’t or will only very reluctantly carry on a conversation in English. Germans may very well speak English, but they often prefer to speak German,” Kjærgaard said.

The other reason that foreign language programs are struggling has to do with a destructive discourse, she believes.

“Language hasn’t been considered a ‘hard’ competency like math. But foreign languages do have a lot of real-world applications, for example in relation to finance, export and industry, and so our discourse about foreign languages has to change,” Kjærgaard said.

And in fact, to determine the level of demand for employees with a command of a foreign language, the Confederation of Danish Industry recently carried out a survey of internationally-oriented member companies. Sixty-two percent of the surveyed companies indicated that they will need employees who speak German within the next five years. For French, the proportion of companies who anticipated a need within the same timeframe was twenty-six percent.

Little funding for research

Johnny Laursen, the dean at Arts, also points out a third challenge facing the universities:

“There is very little research funding available for foreign language subjects and the disciplines involved in language programs.”

Although he would like to discuss the possibility of research collaborations in these fields with various research foundations, it’s been a very long time since any of them have prioritized foreign languages, Laursen added.

“When there isn’t very much external funding, it means there are fewer junior researchers working in these areas. This means these disciplines develop more slowly and there’s less knowledge exchange, because having junior researchers is an asset for a program,” he said.

But according to Laursen, the biggest challenge in relation to reversing the downward trend is a lack of political will to boost language programmes.

“It’s not an easy task. It involves different educational sectors, multiple ministries and many different types of institutions that would have to work together on this. But to be honest, if this were a political priority, a solution would have been found,” Laursen concluded.

The university itself is working to reverse the trend through NCFF. Among other initiatives, AU has gotten involved in a collaboration with NCFF and VIA University College in Aarhus in connection with a teacher training program with a special focus on foreign languages. A similar project has been launched in Copenhagen.

NCFF has also started a variety of initiatives aimed at making foreign languages more relevant for primary and secondary school students and altering the discourse that has led to their devaluation.

For example, the centre sends ‘foreign language ambassadors’ with degrees in these subjects to upper secondary schools to talk about the kinds of careers foreign language skills can lead to, and how many people use foreign language skills in their jobs – including in the sciences - even if their academic background is not in foreign languages per se. NCFF has also produced short videos about fourteen people who use foreign language skills in a variety of careers, from journalism and politics to the opera and the military, in addition to producing educational materials for upper secondary schools. But change won’t happen overnight.

“There are limits to how much you can change a discourse and an educational system in five years. It will take more than five years to reverse this tendency, and it will end up costing a lot more than 100 million kroner,” Kjærgaard said.

We have to coordinate the convoy

Kjærgaard has described the educational system as a “supertanker” that changes course very slowly. Laursen thinks it’s more like a convoy of ships.

“I’m not sure that the supertanker image is the right one, because it implies that there’s one captain, one wheelhouse and one motor. This thing is not nearly as coordinated as a supertanker.”

According to Arts’ dean, what’s needed is a holistic solution that will ensure that foreign languages are embedded in primary schools, secondary schools and universities all over the country.

“What’s happening now is that foreign language programmes are being concentrated in fewer and fewer locations, especially around the capital. This will take political will across the aisle that doesn’t waver over time. In that case the institutions would definitely be able to figure this out together,” Laursen said.

But as the situation stands, efforts are uncoordinated, which brings us back to the convoy.

“I imagine it more like a convoy of ships, and we need to get them to sail in the same direction. That’s a lot of ships that have to change their course at the same time,” he said.

For example, he said, the foreign languages component of teacher training needs to be strengthened in order to make primary and lower secondary school teachers more comfortable with – and better at – foreign languages. By the same token, the universities need to work together with the university colleges that offer teacher training programmes, because the universities supply many of the lecturers who teach foreign languages to coming primary and secondary school teachers. The universities also need to produce upper secondary teachers with the necessary foreign language teaching qualifications. All of these initiatives are necessary to increase applications to language programmes at the universities. But at the same time, they also depend on an increase in applicants for their realization.

“Some educational reforms are necessary. We have to get the entire circle moving. The convoy is turning very, very slowly, and I’m afraid that not all of the ships sail equally fast,” Laursen said.

MORE ON THIS STORY: 7.243 er tilbudt plads på Aarhus Universitet – men især ingeniøruddannelserne og sprogfagene har plads til flere

Educational reforms won’t happen without political support. But unfortunately, the political climate for foreign languages has been chilly for a long time. Although, as Laursen pointed out, there have been a few politicians with an interest in the area.

“Søren Pind established the national foreign languages strategy in 2017. He deserves recognition for that, and it’s in this connection that the resources for NCFF were allocated. But that’s basically the last we ever heard about it,” Laursen said.

Like Kjærgaard, Laursen mentioned the map of municipal schools that offer French. It epitomizes the problem, he thinks. And time is running out.

“A lot of the foreign language teachers at primary and secondary schools are approaching retirement age. The headmasters who offer these subjects have to believe that enough students will sign up for them if they’re to hire new teachers,” he said, tapping the spreadsheet on his desk for emphasis.

“And of the few students who are admitted to an MA program, are there enough who would apply for a job like that? The entire infrastructure is getting more and more fragile. I truly hope that our politicians understand that the situation is very urgent; otherwise it may just be too late to reverse the trend.”

Translated by Lenore Messick