We turn a blind eye to cheating

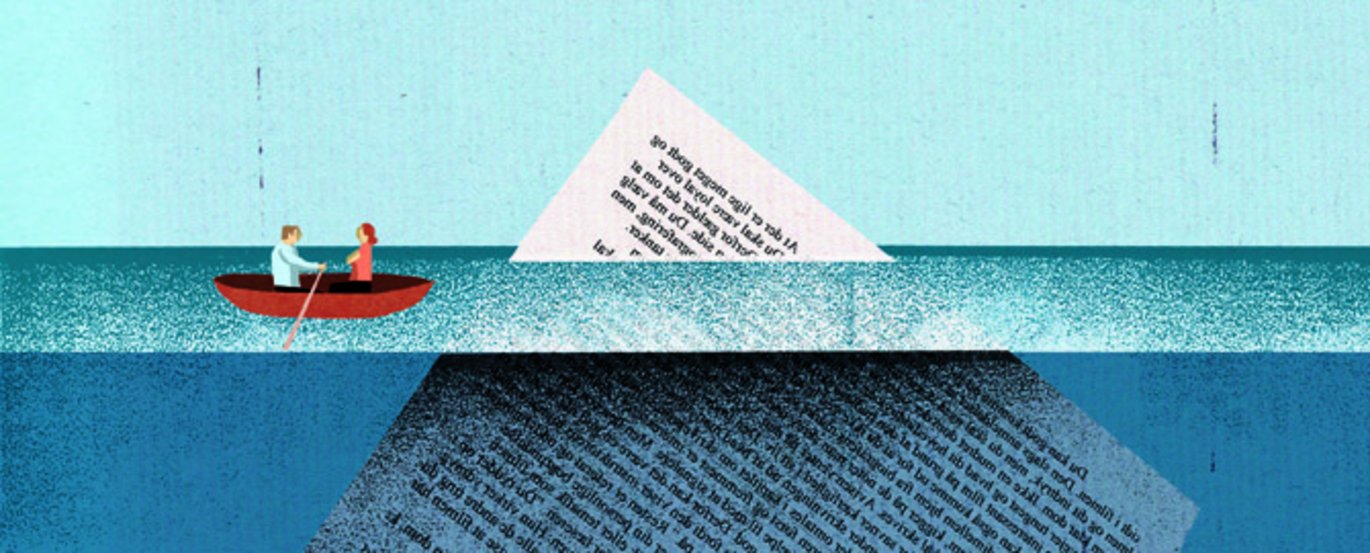

On the way to work one morning I hear on the news that there has been an increase in the number of cases of cheating and plagiarism at the Danish universities. My first thought is that these figures actually cover up a much higher figure, because we only detect the tip of the iceberg.

By associate professor, PhD, Christian Waldstrøm, Department of Business Administration

I base this feeling on my own experience after I had my first case of plagiarism a number of years ago, which made me aware of the problem.

By sharpening my focus I went from having no cases to having two-three cases a year. Today I have my own radar that automatically locks on when the language in one of the student assignments changes from section to section, from grammatically challenged and anaemic to precise, well-founded and maybe even elegant. I also have a methodology that means I ask for all assignments to be delivered electronically and run through our anti-plagiarism system ‘URKUND.’

As it seems pretty unlikely that my students should year after year have poorer morals than those of my colleagues, I embarked on a bit of a crusade to put the problem firmly on the agenda. I used the lunch-break to openly (but in anonymised form) describe the cases I had seen, how I had detected them, and how they had been handled in the Educational Legislation Advisory Service. This has kick-started a development where more and more cases have been uncovered and, not least, reported so that the guilty parties have received appropriate sanctions. This is very much also due to a serious tightening up of the handling of these cases by the administration in recent years, both as far as the handling of cases and the consequences for the students go. In this context what is particularly disheartening is that I have on a number of occasions had students say directly to me - and this is after having received a conviction for plagiarism - that “this is what I’ve been doing throughout my degree programme.” This only reinforces my conviction that the problem is more serious than the statistics show.

A particular challenge when it comes to stamping out the problem is that I meet widely varying attitudes towards cases of cheating and plagiarism around AU. A number of colleagues have said directly that they don’t intend to waste time on reporting but that they simply fail the student and say to them that “now they had been punished by having to resit the exam.” In other places I meet director of studies, and this is especially true of smaller degree programmes, who are very cautious about risking bad publicity and who would rather turn a blind eye than end up with a case that damaged the degree programme’s reputation. Finally you can just see that there are considerable differences in the number of cases that are reported by the various academic environments. Is this solely due to the students having different moral compasses depending on the field of study - or is it due to the existence of different traditions for uncovering and reporting cheating and plagiarism?

AU has created the framework so we can hit back against cheating and plagiarism by setting up a team with the right competencies and special focus on this area, and that is an important first step. But in a year’s time I’d really like to hear the newsreader say that: “During the last year Aarhus University has experienced the largest increase in reports of exam cheating and plagiarism. This is the result of a targeted effort to stamp out the problem.”

Translated by Peter Lambourne