Show me your office – Cathrine Hasse

Cathrine Hasse, anthropologist and professor of education studies, wants to understand how sharing our society with artificial beings like robots affects creative beings like us humans. Who’s setting the agenda? And how?

You immediately feel comfortable in the company of Professor Cathrine Hasse from DPU (the Danish School of Education) – she radiates human warmth and sympathy. And that’s a pretty useful quality for a professor who’s coordinating the interdisciplinary research project REELER, which is exploring the relationship between man and machine.

The project group, which includes researchers from a number of European countries, received a multi-million grant from Horizon 2020, the European framework programme for research. Their focus is the ethical and social challenges associated with robot technology.

This is not the first time Hasse has directed major research projects focussing on the relationship between human beings and technology. For example, she headed the research project Technucation, which explored how people in different professions who use advanced technologies on a daily basis understand technology.

What’s on your desk right now?

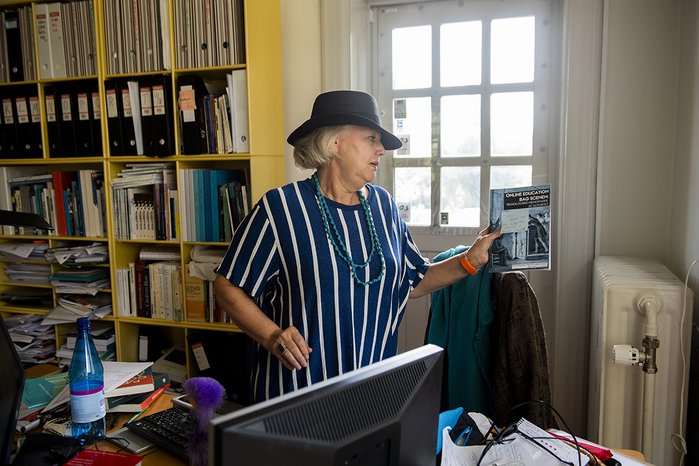

“I haven’t gotten around to straightening up,” Hasse comments, throwing out her arms in a gesture which might include the desk, or the office, or even the whole place – the stately old mansion where she and the rest of her research team work, a stone’s throw from AU’s Emdrup campus.

“I’d rather spend my time starting things up,” she explains.

But then her eye catches a manuscript on her desk.

“Yes, there it is,” she says, picking up the manuscript, a PhD dissertation entitled ‘Online education behind the scenes’, by xx, one of Hasse’s PhD students.

“I think it’s so fantas...no, I’d better not say more, because it’s not been assessed yet.”

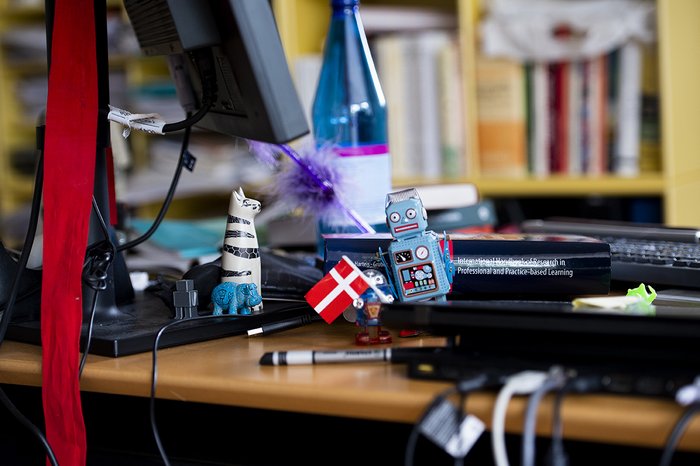

There are robots of all shapes and sizes on the desk, the bookshelf and the windowsill. So you can probably guess how Hasse answers my next question:

What item in your office says the most about you as a researcher?

“All of these little robots I’ve been given by different people in connection with our research programs. This one is a gift from a student,” Hasse says – a blue robot made of tin.

“And this green one is from when we printed out fairytale characters in 3D in connection with a project. Because we have this principle that we don’t write about technology we haven’t worked with ourselves.”

“And I got this guy here with the flag one time when my colleagues surprised me on my birthday. I’m fond of this one and the others too, all of which were given to me as gifts. I think it says something about the relationships we have to each other in the research group.”

What object in your office says most about you as a person?

“That would have to be the cat my daughter gave me. She’s got a thing about cats,” Hasse says. And if her office was burning and she had to get out in a hurry, the cat is what she’d save.

“The hippo is an Egyptian lucky charm my parents gave me a long time ago.”

But the robots and the cat aren’t the only objects in Hasse’s office with a story to tell. There are little curiosities all over the office. Like a black bull, for example.

“It’s from a trip to Spain with my husband. We saw a bullfight, and both of us found watching the bull get killed just revolting, of course. But it was interesting to experience the expression of the most primeval human instincts. And the atmosphere was fantastic.”

Even though almost all of the available surfaces in the office are covered by robots, they aren’t actually the primary research interest for Hasse and her group. Yes, robots and their abilities are half the story. But the other half is human beings and our (lack of) ability to comprehend how fundamentally artificial intelligence will change how we understand ourselves and how we perceive ‘the others’. And by extension how we experience society and the world.

Hasse and her research group have elected to study the relationship between man and machine in a more abstract sense, but from a variety of disciplinary perspectives. They are wrestling with question such as: What can humans do that robots can’t do? And is what robots can do something we humans actually want to use? And if that’s the case, how do we make sure that human beings – or more precisely, different people with a lot of different needs – set the agenda in relation to the increasingly prominent role these machines play in our lives?

“Unlike machines, human beings possess creative intelligence, and our brains are so plastic that we’re some of the most adaptable creatures on earth. This means that we are the ones who will end up adapting to the machines. And so it’s crucial that we take a critical approach – not only to the technology, but to how we develop it as well. Who we involve in the process. And how we deal with the technology in the future.”

What are you going to do after I leave?

“I’m going to a meeting with my whole research group, and afterwards we’re throwing a little party – it’s become a tradition at the end of a semester.”