What is good feedback - and who has the competence to give it?

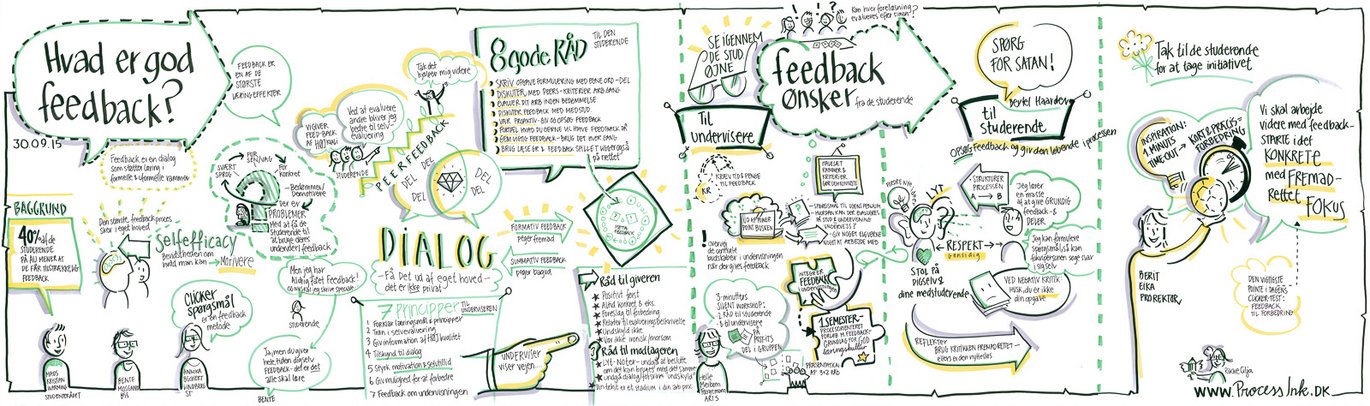

There was no mistaking the commitment as students met to discuss how they could get more feedback on their academic performance. The same was true when teaching staff met to discuss how they could come to give more feedback.

The expert's seven principles for feedback

Omnibus presents seven scientifically-based principles on good feedback that have been drawn up by one of the leading international experts in the field, Emeritus Professor David Nicol from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow. Each principle also includes one piece of important advice.

Nicol’s principles are intended for teachers, but according to Teaching Associate Professor Bente Mosgaard from the Centre for Teaching and Learning (CTL) at Aarhus BSS, students can also benefit greatly from studying the principles.

"If students are familiar with the principles, they can help to qualify a discussion about feedback with the teachers. When David Nicol for example writes that you should ‘Let your students see selected examples of previous assignments’, students can turn this advice on its head, so that it’s directed at them – and read it as ‘ask to see examples of previous assignments.’”

1. Show what characterises a good performance (learning objectives)

- Let your students see selected examples of previous assignments and ask them to judge which is best.

2. Train your students' ability to assess their own skills, knowledge and strategies

- Let your students tell you what type of feedback they want on their assignments.

3. Give high quality feedback

- Make sure that you explicitly relate your feedback to evaluation criteria. This will help your students to link their feedback with the expected learning outcomes.

4. Encourage dialogue

- Ask your students to give each other feedback on their draft versions.

5. Encourage your students’ self-esteem

- Organise assignments as aligned (the degree of coherence between learning objectives, teaching and exams), so your students can practice the skills that will be tested in the exam.

6. Give your students the opportunity to act on feedback

- In your feedback, give the students advice on what they should work on to improve their performance.

7. Use feedback to improve your teaching

- Obtain feedback about the teaching by getting your students to take a minute to write five lines about what they did not understood in the lecture – and use this information when preparing the next lecture.

Find out more about emeritus professor David Nicol’s research at www.reap.ac. uk

"I’ve never received feedback, and I’m about to start my Master's thesis!"

As one of students said in frustration over not receiving feedback at an event with the title "Your feedback means something", which was held at the end of September and drew 22 students to the Student House in Aarhus.

The Student Council had taken the initiative to hold the event together with Pro-Rector for Education Berit Eika and the four learning centres at the faculties.

The background was last years study environment survey from AU, where only forty per cent of the students stated that they received sufficient feedback on their academic work during a semester.

The speakers from the learning centres underlined that it’s difficult for students to learn new things, if they don’t receive confirmation along the way that they’ve understood what they should. Furthermore, feedback also strengthens the students' awareness that they can manage their studies. Feedback therefore helps to both motivate students and strengthen their learning.

Inspiration day for teaching staff

The students aren’t the only ones who are interested in discussing feedback.

Three days after the Student Council's event, ninety members of teaching staff from Aarhus BSS gathered for a day of inspiration on effective feedback organised by the Centre for Teaching and Learning (CTL) at the request of the directors of studies at Aarhus BSS.

The background for the event was explained in the invitation to the teaching staff:

Feedback is one of the most important prerequisites for acquiring new knowledge and developing new skills. This is also true of university students. However, one of the biggest challenges is to ensure that students at Aarhus BSS receive as much and as qualified feedback as possible within the framework that is available for the teachers.”

READ MORE: Lecturer at Political Science: Frustration is a sign of change!

This hit a sore point. Like the students, the teachers also expressed frustration. As one of the lecturers from the Department of Economics and Business Economics put it during one of the day’s workshops:

"I think it's annoying that I get poor feedback from students about the way they receive feedback, when I’ve done a lot of work for free getting it organised."

The teacher had tried to make use of the peer feedback method, which is to say that he had organised teaching so that the students gave feedback to their fellow students. But he found he hadn’t done a good enough job of selling the concept to the students.

Focus on peer feedback

Peer feedback is otherwise the way forward. That was the overall message from one of the leading experts on feedback, Emeritus Professor David Nicol from the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, who gave a presentation at the inspiration day.

Nicol invited the teaching staff to involve the students in the feedback process as early as possible in the studies, and to do it in a manner that gave the students the opportunity to develop their own quality criteria.

READ MORE: Voxpop: When was the last time you received good feedback on an assignment?

The lecturer can do this by instructing the students to give one another feedback on assignments within the same topic. In such a process, what happens is that the students constantly compare their own assignment with their fellow students—and in this way continue to develop their own quality criteria. These criteria will, at the same time, come to interact with the teacher’s quality criteria, stated Nicol.

Good advice to students: Accept feedback the right way

- Listen to your feedback. Take notes. You shouldn’t decide immediately whether you can or cannot use the feedback you receive.

- Don't enter into a dialogue with the fellow students who give you feedback. Don’t try to explain or defend what you have written now.

- Don’t apologise for what you have written – your text represents a stage in your work process.

Good advice to students: Give feedback the right way

- Give positive feedback first.

- Always provide specific examples and arguments to back up what you’re saying.

- Give suggestions for improvements.

- Relate your feedback to the evaluation criteria.

- Don’t apologise for what you say.

- Avoid using irony.

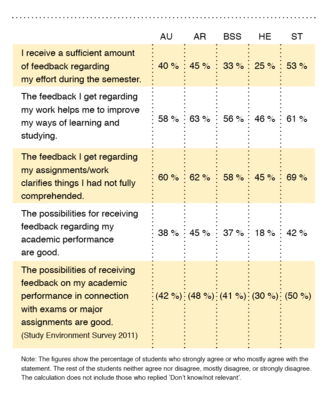

This was how the students who participated in the study environment survey last year responded to the question of feedback:

What can I do better in the future?

That’s the question students really want answered when they receive feedback. At least judging by a small poll among the 22 students who participated in the Student Council's event on feedback at the end of September.

The speakers from the learning centres at the faculties asked the students to think about five questions relating to feedback.

What kind of feedback do you most often receive?

- Joint written (to group/class) 2

- General written – on own performance 2

- Focused written – on own performance 2

- Joint oral feedback 8

- Joint oral – on own performance 7

- Oral feedback – one-to-one 1

Who do you most often receive feedback from?

- Lecturer 6

- Student teacher 8

- Fellow students (peers) 5

- Others 4

How often do you use the feedback you received in future?

- Always 3

- Often 9

- Sometimes 10

- Rarely

- Never

- Not relevant

When you receive feedback, do you know the criteria for a good performance/answer?

- Always 1

- Often 7

- Sometimes 13

- Rarely 1

- Never

- Not relevant

What is most important for your feedback?

- A little, but often

- A lot, but less often 2

- Quick 1

- Know feedback criteria

- Assessment of performance 1

- Future improvements 18

- Is given by lecturer

- Is given by student teacher

- Is given by fellow students

- Is given online

Translated by Peter Lambourne