26-year-old physics PhD: “I can’t see myself working at the university”

Camilla Lønborg Nielsen started her BSc in nanoscience at AU when she was just 17. Just eight disciplined years later, she had her PhD. But now she’s turning her back on the university to take a job in the private sector. Because life as a junior researcher is too uncertain, she feels.

SERIES: FROM A TO PHD

This is the first article in a new Omnibus series that will explore the many paths to a PhD – and not least the hopes and dreams of grad students about the future that awaits them on the other side.

Would you like us to tell your story too? Or know someone else who’d be interested in sharing their story with us? Write to us at omnibus@au.dk.

Until last Friday, Camilla Lønborg Nielsen was part of a research group at the Department of Physics and Astronomy, working to create more effective, gentler radiation therapy for cancer patients. But that’s over now. Despite the fact that her CV reads like a map of a very straight path to a career in academia, she can’t see herself living that life.

Nielsen started kindergarten at the age of six, like most other Danish kids. But unlike most other kids, she skipped a grade, finishing both primary and secondary school in just eleven years. After fifth grade, Nielsen’s parents got jobs in the United States, and because American kids start school a year earlier, she was enrolled in seventh grade along with all the other kids of her age. So when she returned to Denmark two years later, she enrolled in ninth grade, even though her former classmates had only progressed to eighth. She was just 14 when she started gymnasium, and 17 when she started the BSc in nanoscience.

In August, at the age of 26, she earned her PhD in physics and landed a fixed-term postdoc position on the same project. But Nielsen has since left her research team and the university’s yellow brick buildings. Because the life of a researcher is not for her.

“It seems like a hard, uncertain life, where you’re on your alone a lot and constantly have to prove that you’re good enough to continue. It feels thankless somehow,” she told me.

Working in the dark

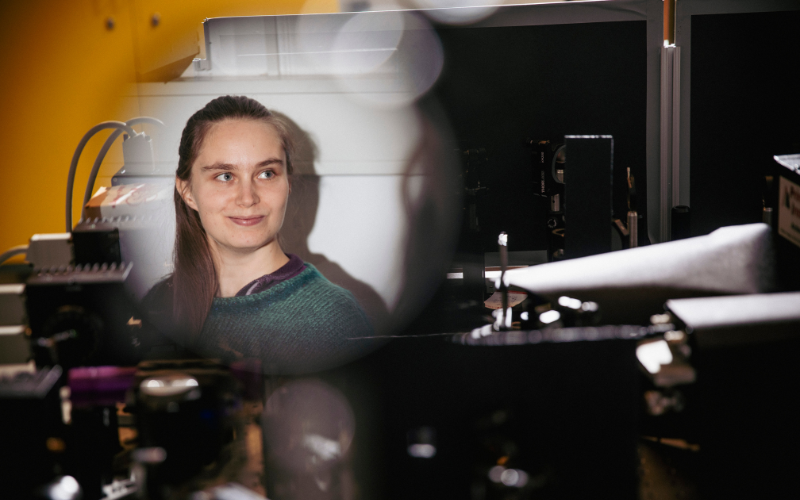

A yellow fluorescent tube is the only light in the lab in the basement of 1522 at the Department of Physics and Astronomy. This is where Lønborg has spent the last five years of her life working towards her PhD. She seems at home here as she shows me the equipment she used to use – a complicated setup with laser beams in a labyrinth of small round mirrors. The light labyrinth stands on a big lab table; Lønborg has spent countless hours of her life next to it. She is so intimately familiar with the table, the mirrors and the room itself that she could find her way around in here blindfolded.

"Over time, I've learned exactly where the cables are on the floor so I can jump over them when the lights are off," she said.

The lone yellow fluorescent tube was once one of four, but the others burned out one by one and were never replaced.

“We use the yellow light when we do experiments with light-sensitive sources because it has a longer wavelength. But I’ve gotten to know the room so well that I don’t even need to turn it on. So when I leave here at four in the afternoon on a summer day, all that sunlight is a real shock for my eyes after a whole day in the dark,” she said.

The search for more precise radiation therapy

The goal of the research project Nielsen worked on as a PhD student and as a postdoc was to develop reusable dosimeters for radiotherapy. A dosimeter is a device that measures the dose of radiation. Typically, photon radiation is used to treat cancer, but Aarhus University Hospital uses proton radiation instead, which is less invasive.

“Photons are X-rays, and they pass right through the human body. So if you’re treating a brain tumour with radiation therapy and want to keep the beam from passing through the tumour and hitting the healthy tissue behind it, you use protons instead,” she explained.

But even though proton beams can deliver a more targeted dose, there’s currently no way to measure the precise dose distribution. As a result, the dose is calculated and delivered based on standard measurements, and it’s not possible to verify whether the beams are actually deposited precisely where you want them from patient to patient.

So Lønborg’s research group set out to develop reusable 3D dosimeters than can be reset after irradiation, which would make it possible to pinpoint precisely where the protons would hit before administering the radiation therapy. A 3D dosimeter shows the precise dose distribution in tissue, which makes it possible to target the tumour more accurately and avoid irradiating surrounding healthy tissue.

"Disposable 3D dosimeters are available today, but they’re impractical and degrade quickly, so they are only used for research. Our team was working on making a cheaper dosimeter that didn’t degrade as fast – and that was above all reusable, so it could be calibrated once and then used basically as easily as a ruler,” Nielsen explained about the project.

A dog eat dog world

While Nielsen described the research project itself with enthusiasm, she was far less enthusiastic when it came to the employment conditions for junior researchers in academia. During her eight years at the university, she learned that landing a permanent position at the university is rare. Knowledge she didn’t have when she started her BSc in nanoscience and hadn’t really considered whether she wanted to pursue a research career herself. As a BSc student, she was part of a research group headed by a 30-year-old researcher with a history of short-term contracts who ended up not getting tenure.

“That’s not the life I want for myself,” Lønborg said.

As a PhD student, she had a chance to immerse herself in the work without worrying about where the next round of funding for the project would come from. But, she said, this is a luxury that tenured researchers don’t have.

“As I see it, in academia the people who are best at doing research are tasked with doing all kinds of other stuff, like teaching and applying for funding. It’s an incredibly competitive and uncertain environment with a lot of people jockeying for position and little money. It’s a dog eat dog world. That's why I can't see myself working at the university - either now or in the long term," she said.

To be in the running for a tenured position, you also have to have done research at another institution outside AU, typically abroad. For Nielsen, that presents an additional barrier; she can’t see herself moving abroad without a guarantee that it would eventually lead to a job at a Danish university. The same goes for her fiancé, who also recently completed a PhD in nanoscience.

“We made a deal that if one of us gets an offer of a research stay abroad in the spring, we’ll consider it. But it’s not something we’re going to actively pursue,” she said.

From radiation researcher to systems engineer

Instead of applying for an extension of her postdoc contract, which expires in May, Nielsen applied for a job in the private sector. And on 15 January, she started her new job as a systems engineer at the high-tech company Terma, which has recently been criticised for supplying technology to the defence industry, including the F-35 fighter jets used by the Israeli military in Gaza. Nielsen is aware of the criticism of the company, but it didn't stop her from accepting the job.

"I’m convinced that Terma is working to ensure that weapons are used better, not just more efficiently and randomly. After all, they design radar systems to detect enemies in your airspace and image recognition in drone images so you can see if there are enemies in the vicinity," she said.

Like leaving a golden egg lying around

When Nielsen left her office at AU for the last time on Friday, it was with the knowledge that the 3D dosimeter she had been working on for four years might never see the light of day: the money for the project has run out.

However, the group is in the process of applying for a patent for their invention of the reusable 3D dosimeter. It's a race against time to beat other researchers who are also working to develop and commercialise a dosimeter to the finish line.

"We’ll just have to see what the patent authorities have to say about it. It feels a bit like leaving a golden egg lying around and hoping you can pick it up before someone else comes along and runs off with it," Lønborg said.

And even though she regrets that her time in the basement of the physics department is over, Nielsen is closing the door to the university with her eyes wide open and her head held high.

"I've been in school non-stop since I was six years old. The past several years I’ve been gradually transitioning to my professional life, because both the PhD and postdoc are a mix of work and study. So now it will be fun to see if I can figure out how to not be a student anymore. I’m pretty sure it’ll work out fine,” she said.