AU researcher captures censured voices from Chinese social media and gives them new life as art

In July, Winnie Soon received a major international award for her three-part work Unerasable Characters Series, which explores the politics of state-enacted censorship and surveillance in a digital age. Soon is both an artist and an associate professor at the Department of Digital Design and Information Studies at AU.

“Soon ultimately questions whether the very same technology that aims to remove information can be hijacked to make the erased unerasable.”

This is how the jury that awarded the Golden Nica in the category Artificial Intelligence and Life Art to Hong Kong-born artist-coder and AU researcher Winnie Soon described her work. She won the award in the Prix Ars Electronica, the oldest media art competition in the world.

The three works in the Unerasable Characters series are all based on content erased/censured on Weibo, one of the largest social media platforms in China. The Chinese government removes thousands of posts from the platform every day, erasing citizens’ voices from the public domain.

To retrieve these voices, Soon used a system called Weiboscope which was developed by Dr. King-Wa Fu at the University of Hong Kong. The system has regularly sampled timelines of a set of selected Chinese microbloggers who have more than 1,000 followers or whose posts are frequently censored. This is how Soon was able to retrieve the content before it was censored. The unheard voices can be heard. But not without distortion. Soon’s work presents Chinese characters from the censured posts in a random jumble or presents posts whole, but obscured, in an ironic gesture that both repeats and exposes the censorship imposed by the Chinese state on the original material.

Soon hopes that her work will inspire her audience to think about what they encounter – and do not encounter – on the internet and social media, she said:

“I play with this tension between something that can be erased and something that can’t be. I address censorship and filtering algorithms within the Chinese context, but that’s just my point of departure. I see this as just as much of a problem in a global context in relation to censorship in Turkey, Russia and lots of other countries and in relation to filtering algorithms. Hopefully, the audience will think twice about what they see on the internet and that what’s presented to you is the result of some kind of filtering process,” Soon said.

Self-censorship in Hong Kong

Despite the international perspective of the work, Soon is particularly marked by their childhood in Hong Kong and the fact that mainland China’s grip has been tightening in recent years:

“Lately I’ve been watching the political situation change in Hong Kong, and a lot of my friends are starting to get worried. People impose censorship on themselves. But the fact that the state or various social media in China censor texts is nothing new. I’ve based my work on an empirical approach. The censored data in ‘Unerasable Characters I’ was retried and stored over the course of a year. The poetry of my work is based on the data I’ve collected. And we can reflect on it from this starting point,” Soon said.

Soon has been informed that exhibiting the entire work in Hong Kong is an impossibility. Even though the Chinese regime has not interfered in Soon’s works, self-censorship has intensified in Hong Kong since the national security law was imposed in 2020 amid massive protests from citizens and human rights organisations. Soon herself began reflecting on the meaning of censorship in 2016:

“I started thinking about what it means to delete something. If we think about this in terms of the state or a company removing something, we tend to think of it in terms of deletion: ‘Your data has been deleted’. But in the digital world, it’s not that easy to delete something. If you lose the data on a hard drive, for example, someone can recover it,” she said.

FACTS: Winnie Soon

Winnie Soon is associate professor at Department of Digital Design and Information Studies and is affiliated with the Digital Aesthetics Research Center (DARC). They also earned their PhD in Software (Art) Studies from AU in 2017. Soon is based in Denmark and London and is currently teaching at the Creative Computing Institute at the University of the Arts London.

Soon's research and practice intersects with art and technology in the areas of Software Studies and Computational Cultures. They are also an ‘artist coder’ engaging with themes such as Free and Open Source Culture, Coding Otherwise, digital censorship and minor technology.

Soon has exhibited their work in museums, galleries and at festivals, and has received numerous awards. Read more about Soon’s research and art here.

Blank paper

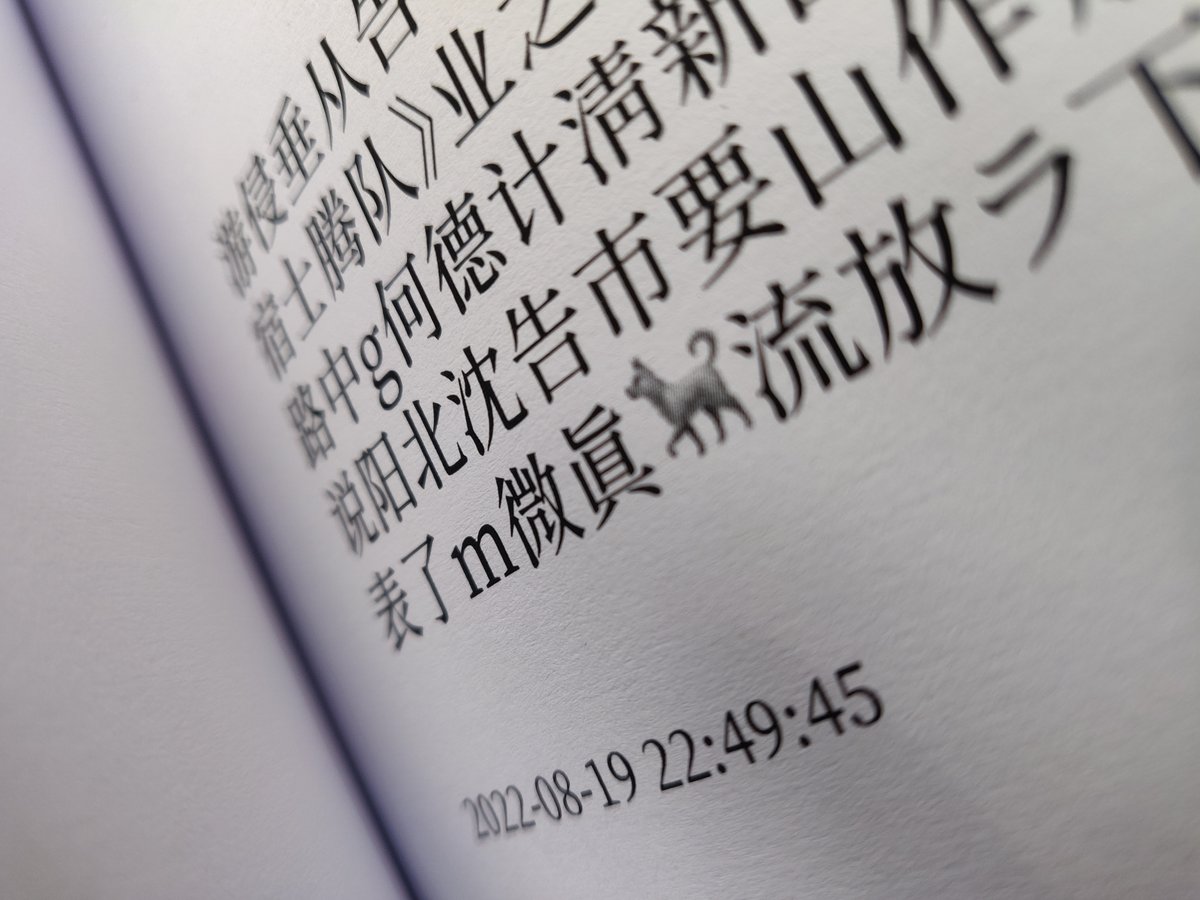

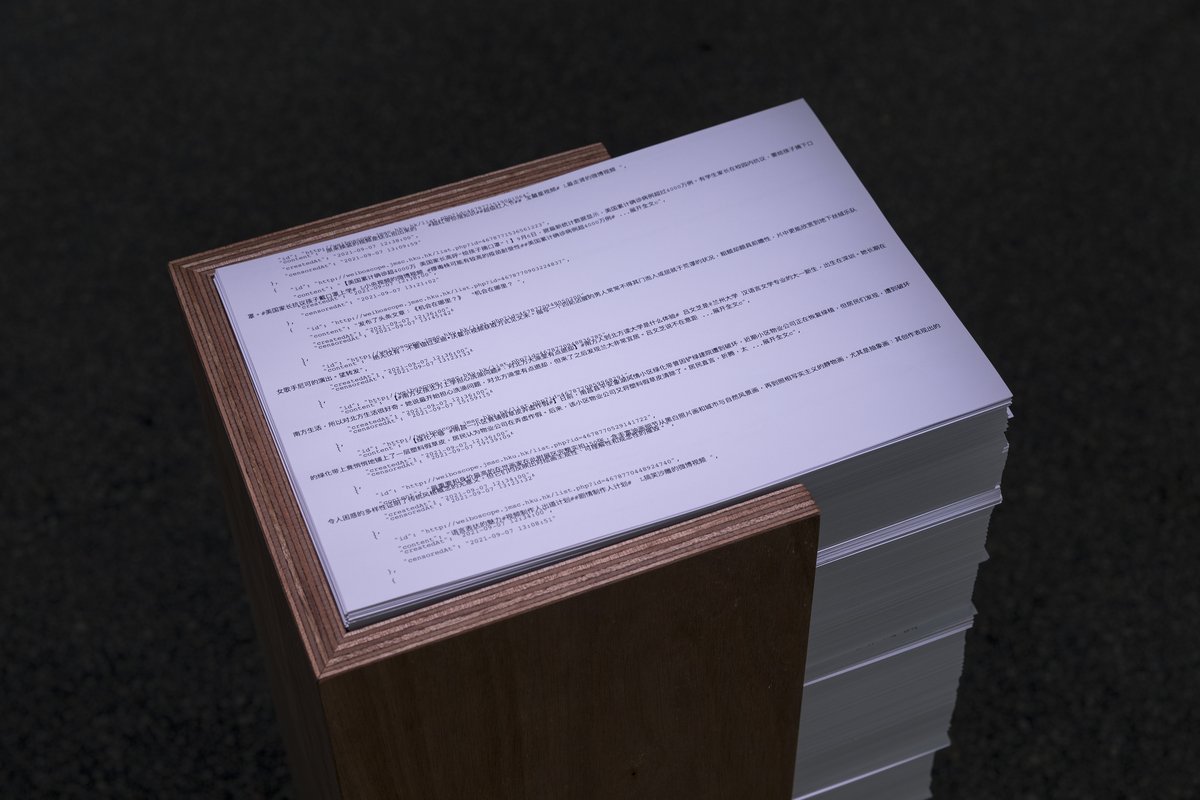

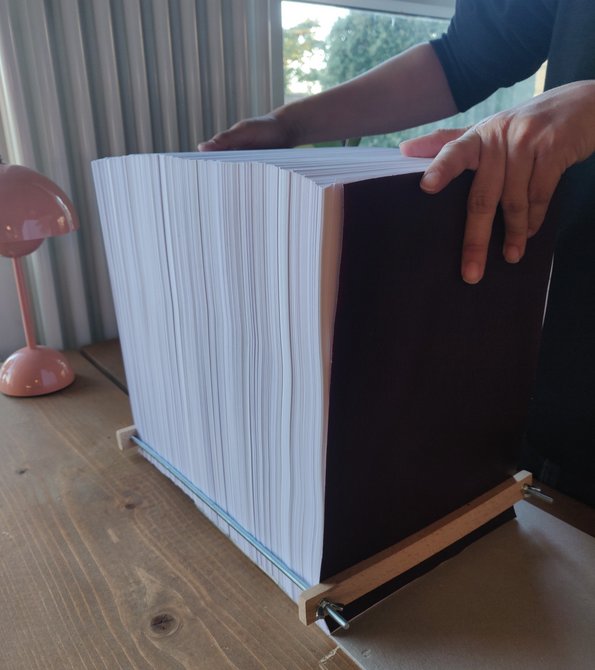

In ‘Unerasable Characters I’, Soon presents 54,064 censured posts on over 6,000 printed pages stacked in a pile on the floor. The posts were collected over a year, from June 2021 to June 2022. Soon also ran the posts through a machine-learning tool that remixed them into illegible strings of characters that Soon then had bound into a book. One source of inspiration for this work is the sheets of blank paper that became a symbol of the demonstrations in Hong Kong in 2020 and again in 2022 in mainland China, when people used them to protest the Covid restrictions. The work forces the viewer to ask whether the book is forbidden, just as the posts it contains were. Soon said:

“By using machine learning, the software in ‘Unerasable Characters I’, I generated text that’s unreadable. I can’t get any meaning out of it. This was inspired by the white paper protest and the blank paper revolution, which have been prominent in recent years, for example in China, Great Britain and Russia. Activists or demonstrators hold up blank sheets of paper. We can’t read it, but we know what they’re protesting against. So it’s not so much a question of what’s written there. So the work asks whether it’s necessary for the audience to know precisely what’s being censored."

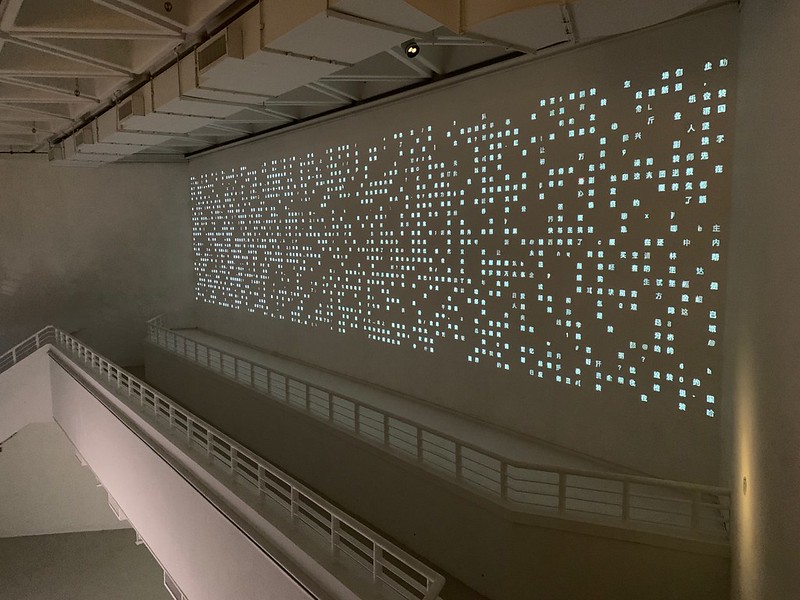

"As an artist, I’m preoccupied not just with focusing on specific or individual content, but on the multitudes of unheard voices. If you only see your own account on social media being manipulated, then you might think: Ok, that’s just one. You can’t really sense the extent of it and the effects. But when I put thousands of censored posts up on a wall, you know – even though you can’t read them – how massive the censorship is. I’m interesting in creating this poetic experience and creating a space for the public can think about the effects of imposed silence.”

Data from the Covid outbreak in China

'Unerasable Characters II' and 'Unerasable Characters III' are purely digital works. In ‘II’, the individual characters from the censored posts are projected on to the wall of the museum, constantly changing and flashing back and forth.

‘III’ is a web page. In the exhibit, visitors can sit down at a computer and follow the many censored posts removed between 1 December 2019 and 27 February 2020, during the first Covid outbreak in China. During this period, 11.3 million posts were published on Weibo: 1.2 million posts contained at least one word about the Covid outbreak, and 2,104 of those posts were censored, according to researchers from the University of Hong Kong. On the web page, the text has been crossed out and the time stamps are blurred. Only the punctuation, special characters and emojis are visible.

The screen freezes periodically to give the viewer time to think about time and space in a digital world that is characterised by systematised processes and political infrastructure, not least in China. Winnie Soon uses the horizontal view to pull the audience away from the endless vertical scrolling we’re so used to from your mobile and computer.

Soon: Art can show us new angles on research

Like Dr King-wa Fu’s Weiboscope system, Soon’s works are open source: users can access all of the data.

“All my work is free and open source. I show my works at museums, but you can also go online and find my data. Artists or researchers can use it,” Soon said.

Soon began working with web design at an early age, and they also found it natural to work with the digital elements of her artworks as a researcher who works with software and coding.

Making the data behind the works accessible to the public leads Soon to ideas about merging art and research that can provide a new look at research questions. Because it’s important for research that the questions are interesting, Soon believes:

"When it comes to research, we need to have a question we want to investigate and a method for approaching it,” she said. “A lot of researchers will conduct interviews or do fieldwork. Others may want to take a historical or philosophical approach. For me when it comes to method, it just happens to be doing something practical: making things and programming them.

What I find exciting about artistic representation and art research is that there are many more ways to approach a question. As teachers, we should think about different ways of presenting a problem to students. It shouldn’t just be, now read this book or article. Art creates a different way of engaging with a social issue that’s more open and less text-heavy. Art fosters a different way of looking at these issues and provokes reflection.”