What’s it to be? A time machine – no problem!

Esben and Erik never say no to a scientist who comes by the office with a crazy idea. The two research technicians at the Department of Chemistry can make anything – almost. And if they can’t, they know someone who can. They will return to a renovated workshop and brand-new machines in September.

A three-metre-wide and three-metre-high hole in the wall of the chemistry workshop testifies to the fact that there are still a few days to go before research technicians Esben Fræer and Erik Ejler Pedersen can return to their familiar surroundings at the Department of Chemistry.

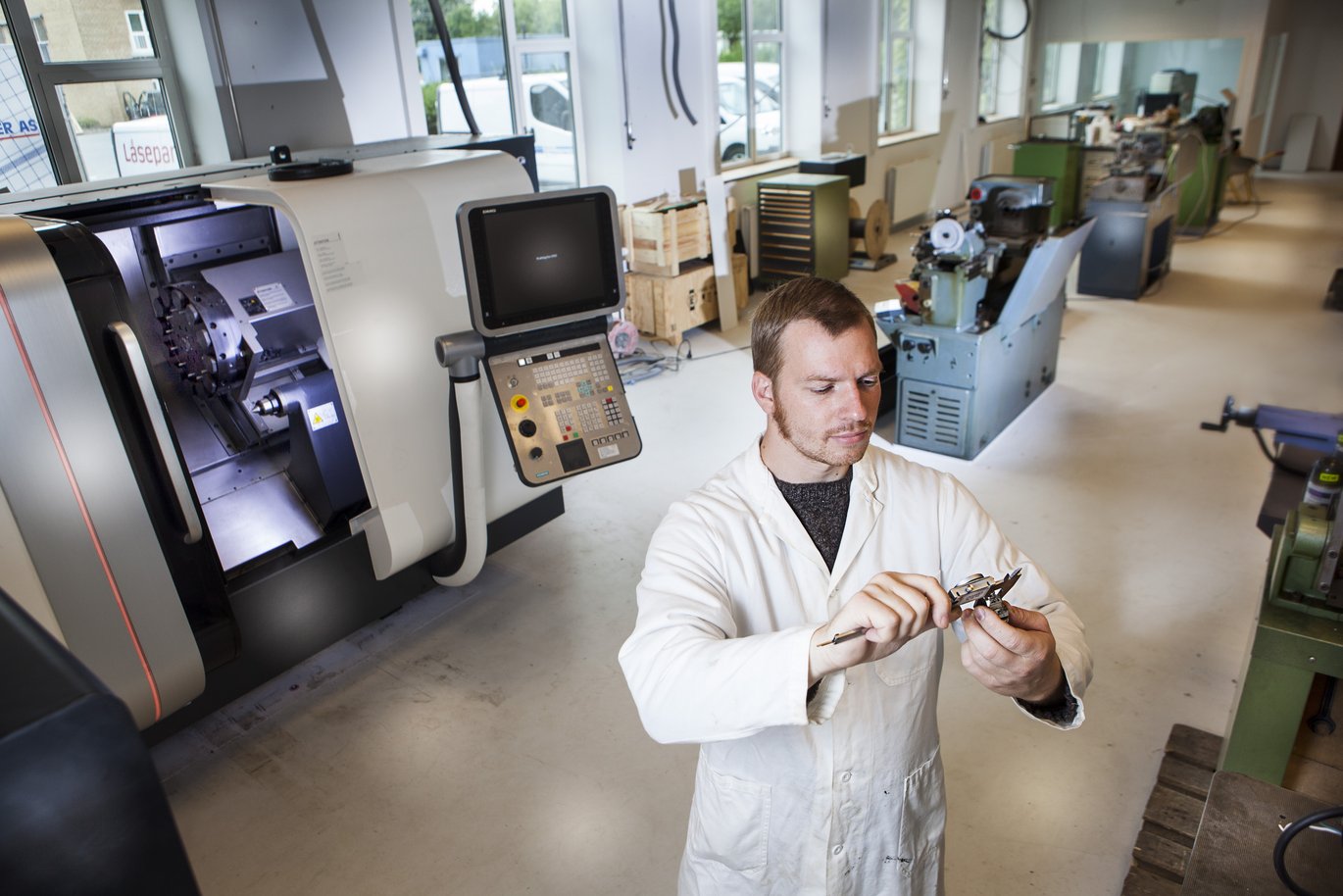

The hole in the wall was necessary to ease the workshop’s two new crown jewels into place: A state-of-the art computer-controlled milling machine and an equally advanced lathe. The machines were shipped from Bielefeld in Germany and cost around a million Danish kroner each.

"We are so looking forward to using them,” says Esben Fræer enthusiastically and runs his hand along the side of one of the two new-smelling rectangular giants – the lathe.

A little further back in the workshop is a fifty-year-old, more modest version of a lathe made of iron with a manual crank handle.

The two are obviously worlds apart says Erik Ejler Pedersen. "You could say that this one is like a Mercedes with all the newest options," he explains pedagogically, when Omnibus’ reporter realises that they are basically the same type of machine.

The coffee machine is the most important machine

"Let’s have a cup of coffee," suggests Erik, thus kindly relieving this reporter of the burden of additional technical details.

It is a quarter past nine. Omnibus has disturbed the few peaceful hours that Esben and Erik have during the day. The two research technicians usually start work at 8:00 and have an hour and a half to follow up on the previous day’s projects before researchers and students begin showing up with all kinds of requests – from the reasonable to the implausible.

And when the ‘customers’ begin showing up the coffee machine turns out to be more important than even the most advanced and expensive machinery, says Esben with a smile as he makes freshly-brewed coffee:

"Sitting and talking over a cup of coffee is when things get interesting and we develop ideas with the customers," he says.

Erik adds: "But researchers can be very up in the clouds and not at all specific. They often show a measurement with their hands like this…"

"…so you have to hurry up and guestimate and write it down," says Esben.

Often the closest thing to take notes on is a napkin. So a lot of research equipment has therefore started life as squiggles on a Post-IT note or a coffee-stained napkin before Esben and Erik make 3D models on the computer.

Tortoise brains and cloud formation

Esben and Erik describe the bits and bobs and devices they have manufactured in their workshop with enthusiasm. The two colleagues supplement each other's sentences and politely let each other interrupt.

What is the strangest thing you have made?

"An apparatus to hold a tortoise brain with eyes that needed to be analysed in a NMR scanner is probably among the more bizarre projects", says Esben. Erik nods and continues:

"A tortoise actually has a hibernation mode that means you can dissect eyes and brain and remove them, and they’re still active! The task was to find a way to fix the brain and eyes in a net while isotopic salt water was passed through them."

The researchers used the experiment to try and find out what happens when turtles go into hibernation in order to use this knowledge in relation to cooling down patients with brain hemorrhages or blood clots on the brain, explain the two research technicians.

Other tasks are simpler. Such as shortening some screws, which Erik will be doing later that day. But even the most basic tasks seem to have a touch of something special and esoteric and vaguely sci-fi. The screws are an important component of research into cloud formation.

Back to the future

Are you inventors?

"You could say that. We find solutions that the researchers cannot come up with themselves. We try to make things specific. So we’ve become good at thinking out of the researcher’s box and into to something tangible," says Erik.

But the ideas have to come from the researchers themselves, says Esben. It’s the researcher's job to find out what purpose things should have and how they should function in theory.

"The researchers rarely have a concept of how something should actually look. But if they come and say ‘We need a sort of flux capacitor’ or whatever it’s called in the film Back to the Future and if they can describe how it will function, then we’ll find a way to build one," he says with a twinkle in his eye.

Esben and Erik still have not yet received a request for a time machine. But if they do they will certainly not give up before they have done all they can to build it.

"We always try first. But of course we sometimes get asked to make things that can’t be made with our machines. So then we help the researcher find someone who can. No one comes to us in vain," says Erik.

Aesthetics, thank you

Even though Esben and Erik share a workshop they work on their tasks as a rule individually. But they know each other's strengths and weaknesses well and rely on each other for good advice and ideas.

And they don’t just exchange ideas on a professional level.

What do you talk about apart from work?

"We don’t talk about politics much as that’s an area where we strongly disagree. But history and philosophy are common interests," says Esben.

Erik nods thoughtfully.

"Yes, we completely agree that the individual must make their own choices – thanks to Kirkegaard and Sartre. I think that the whole question of making a choice is interesting. You have to make a choice. Otherwise what are you? I’ve often experienced people who couldn't figure out how to do that," he says.

"We’ve also just discussed some of Løgstrup’s (Danish theologian and philosopher, ed.) principles," says Esben.

That was during a long drive home from Bielefeld where the two colleagues had been on a course to learn how to operate the new machines.

Their interest in the ideal and sublime is unmistakeable in the day-to-day work in Esben and Erik's workshop.

"We are aesthetes, and that might be our biggest weakness," says Esben, laughing.

"But things have to look good. What if one of our PhD students ends up winning the Nobel Prize using one of these devices? It’d be a shame to stand there in Stockholm with some old gauges stuck on a bit of plywood sheeting."

Solidum petit in profundis

While it might not be art, Esben and Erik's collaboration with the researchers paves the way for new scientific discoveries.

How important the two technicians are for basic research is a question that they would rather not answer. So Omnibus visits some of the researchers at the department.

One of them is Jacob Becker, manager of the Centre for Materials Crystallography. Last year he visited Esben and Erik with an A4 notepad and a pen at the ready. He needed a special extension, a helium spray cooler, for a vacuum X-ray diffractometer. Esben made one for him and according to Jacob Becker, its significance was "absolutely essential".

"It moves our basic research forward and improves our understanding of the behaviour of electrons and chemical bonds in crystalline materials," he says.

Chemistry PhD student Naja Villadsen also met the two research technicians over a cup of coffee when her standard equipment couldn’t do the job.

"When we are testing limits in science we often need some equipment that doesn’t exist yet so we can take that last step. You can always get help at our workshop," she says.

Even though Esben’s and Erik's devices, magazines, holders and other ingenious gadgets are critically important according to the researchers, you are not going to find the research technicians’ names in the scientific articles.

But Esben and Erik are quite happy to stay behind the scenes.

"I feel that you are doing something for the common good and making a contribution to society," says Esben.

Translated by Peter Lambourne.