"Yes, but can it be done?"

There are times when you feel like sitting down in a quiet corner, hanging a “Do not disturb” sign around your neck, and simply watching what’s going on around you. That’s what it’s like in glassblower Jens Christian Kondrup’s workshop at the Department of Chemistry.

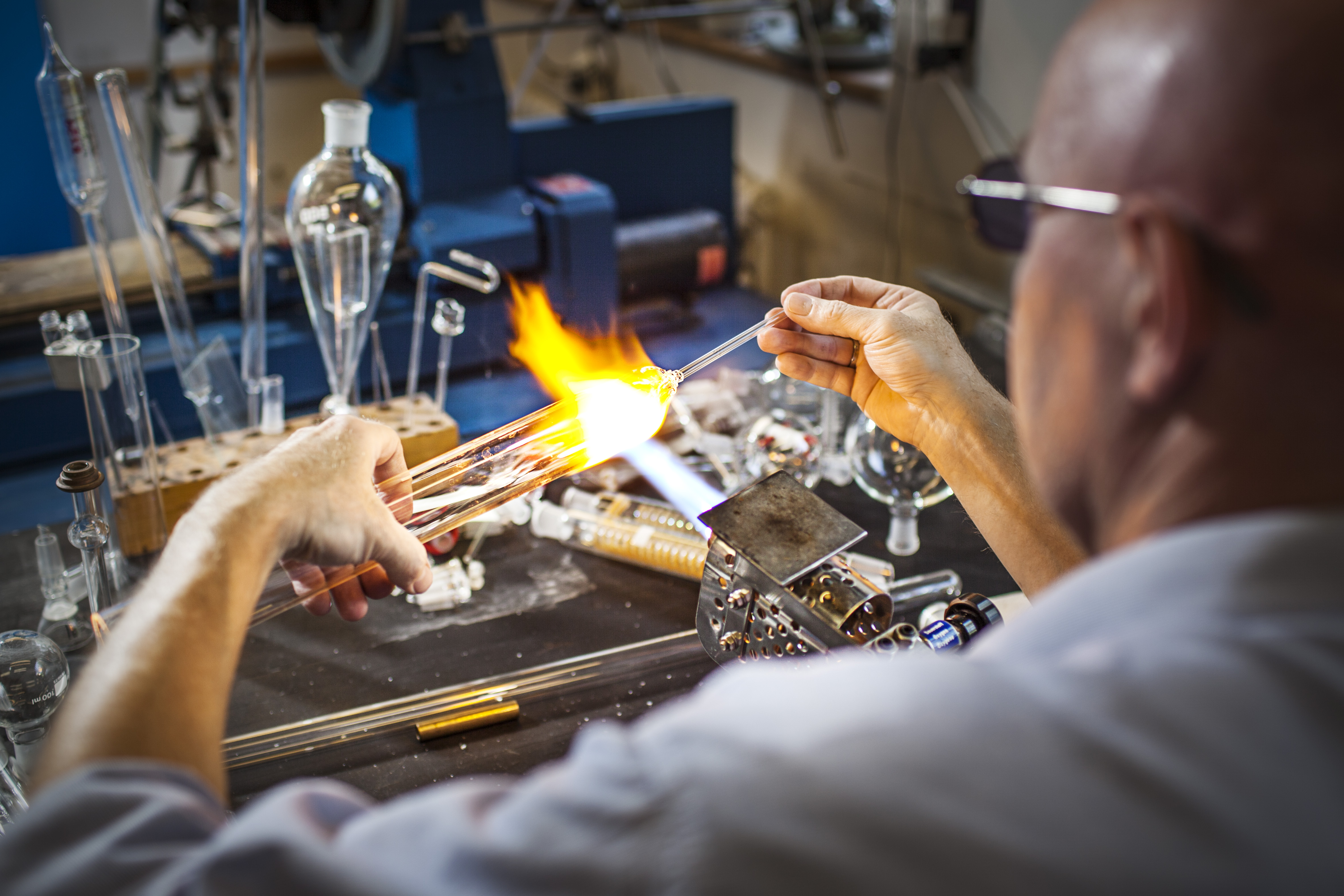

The flame from the burner is heating up the small glass tube that glassblower Jens Christian Kondrup is holding between his fingers. With soft, confident movements he makes sure that the yellow flame is distributed evenly across the entire surface of the glass.

“Glass is one of the most fantastic materials I know because you can shape it really fast – unlike many other materials. But this also means that you need to know what you’re doing, because otherwise you quickly run into problems. And things do sometimes go wrong for me and a crack appears – typically at the most difficult spot in a complex structure,” explains Kondrup. Last year he celebrated his 25th anniversary as a glassblower at the Department of Chemistry.

A shattering experience

He’s an experienced craftsman, and is always annoyed when his glass cracks because he knows that before this happens the glass always gives a warning signal that he must have overheard.

“Glass talks to you just before it breaks – it gives off a particular ‘ping’ sound. As a young man I worked in a workshop with ten other glassblowers, and we all used to freeze when we heard that sound. We stopped what we were doing, wondering whether it was our own glass or someone else’s that was just about to shatter.”

A new kind of test tube

The flame does its job, and the small glass tube begins to turn into a test tube in Kondrup’s expert hands. This is a routine task for him.

“But just before you came in I was working on a brand-new type of glass tube. It’s not completely round, so the heat works slightly differently and I need to be a bit more careful because I’m still getting to know what it’s like. But once I’ve tried it 10-20 times I can start working faster because by then I know exactly how to apply the heat to that particular shape of glass.”

Qualified feedback

Kondrup explains that the best thing about working at the university is the variety of his job. And he is always delighted when the researchers ask him to produce something special to help them do their research – either in the lab in Aarhus, or on a research vessel at sea.

What I enjoy most is when they say ‘Yes, but can it be done?’ And when I’m able to give them qualified feedback – whether they’re scientific researchers, doctors or PhD students.”

The flask of tomorrow

Kondrup would like to teach the researchers a bit more about the nature of glass.

“Lots of people ask if they can watch me while I work, which suits me fine because it means they will learn a bit more about what glass can do. They get ideas when I make something special, and start wondering what else I could make if they asked me. I try to teach them about the huge range of possibilities. Just because a flask looks like this today, it doesn’t mean it has to look the same tomorrow.”

PhD students

In particular, Kondrup would like to help PhD students to understand the full potential of glass. He works closely with many of these students during the initial stages of new research groups.

“I work with them a lot when they’re trying to get their project off the ground, and of course I’m involved when they need me to make special glass structures. Later on I’m only involved in maintenance jobs. But I love being part of their everyday work – for instance when some young researcher tells me he’s finding it hard to keep his material stable and I suggest wrapping a hot casing around the flask he’s using. ‘Yes, but can it be done?’ they ask in amazement.”

PhD defences

During the past five years, Kondrup has started to attend one or two PhD defences each year.

“After working closely with a group of researchers, it’s always interesting to hear how they present their findings.”

But the glassblower has a particular fondness for working with experienced researchers like Professor Niels Peter Revsbech, who has just been presented with the 2013 Grundfos Award for his work in developing micro-sensors and his research into microbiology on the seabed.

Blimey, it works!

“One of things people praise Revsbech for is that his special electrodes are capable of carrying out measurements at a depth of 900 metres below sea level, enabling him to determine the concentration of oxygen at that kind of depth. This has never been possible before, and it actually takes place in a glass structure that I made in close collaboration with Revsbech. That kind of thing fills me with professional pride: hearing other people praising an excellent research project in which I have played a small part,” smiles Kondrup. And he continues:

“Revsbech is great, because he’s the kind of person who gives you feedback. When he was on a marine expedition to carry out his measurements, he took the time to send me a mail just to say ‘Blimey, it works’.”

About Jens Christian Kondrup

- 50 years old

- Completed his training as a glassblower in 1984

- Appointed at AU in 1987

Translated by Nicholas Wrigley