THE COMMITTEE FOR MASTER’S DEGREE PROGRAMMES IN NEW INTERIM REPORT: IN THE FUTURE, ONE IN FOUR STUDENTS MIGHT HAVE A SHORT MASTER'S DEGREE

The universities do not believe that converting 20 per cent of admissions to Master's degree programmes for working professionals is attainable. As a result, many more students than anticipated might end up taking a one-year Master’s programme. All rector’s agree that the premise regarding labour supply must be changed.

According the interim report published by the Committee for Master’s Degree Programmes on Wednesday, the proposed reorganisation of the programmes that would entail ten percent of students being admitted to one-year Master's degree programmes may in fact affect up to one in four students.

The Committee for Master’s Degree Programmes was set up by the parties behind the reform and is tasked with designing the new educational landscape that the reform envisages.

The goal of the agreement is to convert 10 per cent of admissions to shorter one-year Master's programmes totalling 75 ECTS credits and convert 20 per cent to two different types of Master's degree programmes for working professionals: a flexible Master's degree for working professionals and a career-focused Master’s degree programme with work placement. The terms of funding included in the agreement mean that 30 per cent must be converted regardless, so if there are fewer students on programmes for working professionals, then there need to be more students on the one-year programmes.

And as the interim report now shows, the universities do not consider it realistic to have so many students on the programmes for working professionals. The financials of last year's Master’s reform are simply not set up to make this possible, say the universities.

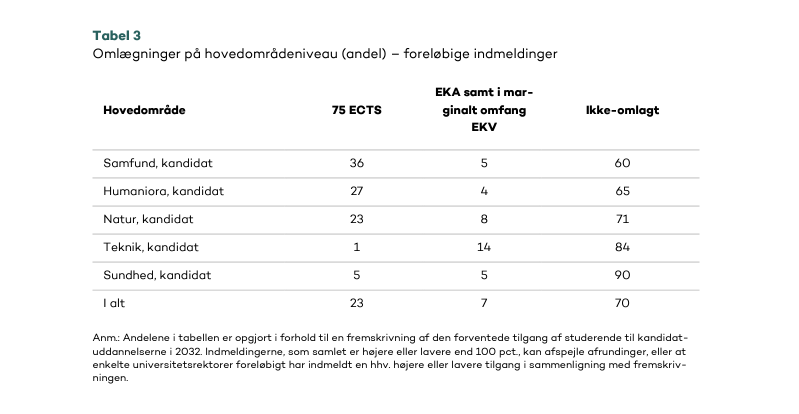

According to the rectors of Danish universities, who are all members of the committee, they only expect seven per cent of students will be admitted to a Master's degree programme for working professionals in the future, while 23 per cent will be admitted to a one-year Master's degree.

The rectors make a number of comments in the interim report, including that the political intention of converting 20 per cent of admissions to Master's degree programmes for working professionals will be a challenge:

"The university rectors also indicate that if the premise of delivering labour supply is not changed, then the universities will probably choose to convert a significant portion of their Master's programmes to the shorter Master's programmes worth 75 ECTS credits. This could potentially make it difficult to realise the political intention of seeing 20 per cent of all Master’s students taking a career-focused Master’s degree.”

NOTE ENOUGH MONEY FOR THE REFORM

In a column in Altinget on Wednesday, AU Rector Brian Bech Nielsen and SDU Rector Jens Ringmose explain that the problem is that the 20 per cent of students on a future career-focused Master’s degree programme must provide the same labour supply as had they been admitted to a one-year Master's programme. This means that students would be burdened with up to 60 hour work weeks.

"The consequence of the reform will be an increase of short Master's programmes, and our estimate is that almost a quarter of future students will leave university with a one-year Master's degree. Shortening so many programmes is an extremely risky experiment and goes against the objectives of the political agreement. We therefor ask that the premise of the reform be altered," write the two rectors in the column.

Career-focused Master’s degree programmes can be planned within a range of 75-120 ECTS credits, and the Master’s degree committee is considering both the flexible Master's degree programmes for working professionals and career-focused Master’s degree programmes with work placement.

According to the rectors and the two representatives from the National Union of Students in Denmark who are also on the committee, none of the nine proposed models for the Master's degree programme for working professionals with work placement are realistic "due to the overall workload of the student”. With regard to the other Master's degree programme for working professionals, the same stakeholders note that "a general programme model for a flexible Master's degree for working professionals that is less than four years long is not realistic when the programme must be worth 120 ECTS credits and the total workload for the student must not exceed the labour market norm".

CONCERN FOR THE EMERGENCE OF AN A TEAM AND B TEAM

While much of the reform has yet to be discussed in depth by the committee, and "significant work remains to be done, including coordination between universities, before the committee can make its final recommendations for the future of the educational landscape for Master’s degrees", several points in the report provide new insight into how the Master’s reform may unfold.

For example, all universities recommend that graduates from one-year degree programmes have the word brevis (short) added to their title.

“This would help clarify the type of degree programme to future employers and signal that it’s a 75 ECTS programme,” the report argues.

On the other hand, representatives from the Ministry of Higher Education and Science, the Danish Agency for Higher Education and Science and the National Union of Students in Denmark, believe that no distinction should be made, as "this could potentially contribute to a perception of an A team and a B team."

The committee also recommends that the final assignment for the shorter Master's programme should not be called a thesis but instead be called 'final research project'. Because the Master's programme only corresponds to 75 ECTS credits, it is not as specialised as two-year Master's programmes, and this should be reflected in the name.

The Committee for Master’s Degree Programmes will present its final report in October 2024. The interim report also states that, ahead of submission, the committee will discuss the following: the quality, administration and organisation of the new Master's programmes, new opportunities for lifelong learning and research tracks.

The first students on one-year Master’s programmes will be admitted in 2028. This means that students who start a Bachelor's programme next year will be the first who can be admitted to a one-year Master's programme.

Members of the Committee for Master’s Degree Programmes:

- Chair Hanne Meldgaard, permanent secretary at the Ministry of Higher Education and Science

- Janus Breck (deputy chair), director at the Ministry of Higher Education and Science

- Mikkel Leihardt, director general of the Danish Agency for Higher Education and Science

- Martin Madsen, deputy director of the Danish Agency for Higher Education and Science

- Henrik Wegener, rector of the University of Copenhagen

- Brian Bech Nielsen, rector of Aarhus University

- Jens Ringsmose, rector of the University of Southern Denmark

- Per Michael Johansen, rector of Aalborg University

- Anders Bjarklev, rector of the Technical University of Denmark

- Peter Møllgaard, rector at Copenhagen Business School

- Hanne Leth Andersen, rector of Roskilde University

- Per Bruun Brockhoff, rector of the IT University of Copenhagen

- Esben Bjørn Salmonsen, chair of the National Union of Students in Denmark

- Lauge Lunding Bach, educational policy deputy chair of the National Union of Danish Students

- Jesper Langergaard (observer), director of Universities Denmark.

Source: Committee for Master’s Degree Programmes