Gender equality expert: New talent programme for women is a symbolic gesture

Individual talent programmes such as the new Inge Lehmann programme are god news for the few women who receive grants from them. But the programme is a symbolic gesture that won’t make much of a difference in addressing gender balance at Danish universities. What’s needed are long-term initiatives, says Evanthia K. Schmidt, associate professor and director of the Danish Centre for Studies in Research and Research Policy at AU.

The Inge Lehmann programme

- The purpose of the programme programme is to promote talent development in Danish research by fostering a higher degree of gender equality in academia in Denmark.

- The Inge Lehmann programme will award 20 million kroner in grants annually.

- Researchers from all fields – men and women – are eligible to apply for funding from the programme. Female applicants can take priority over male applicants in cases in which both are equally qualified.

- The programme is names after the woman seismologist and state geodesist Inge Lehmann, who demonstrated that Earth has a solid inner core in 1936.

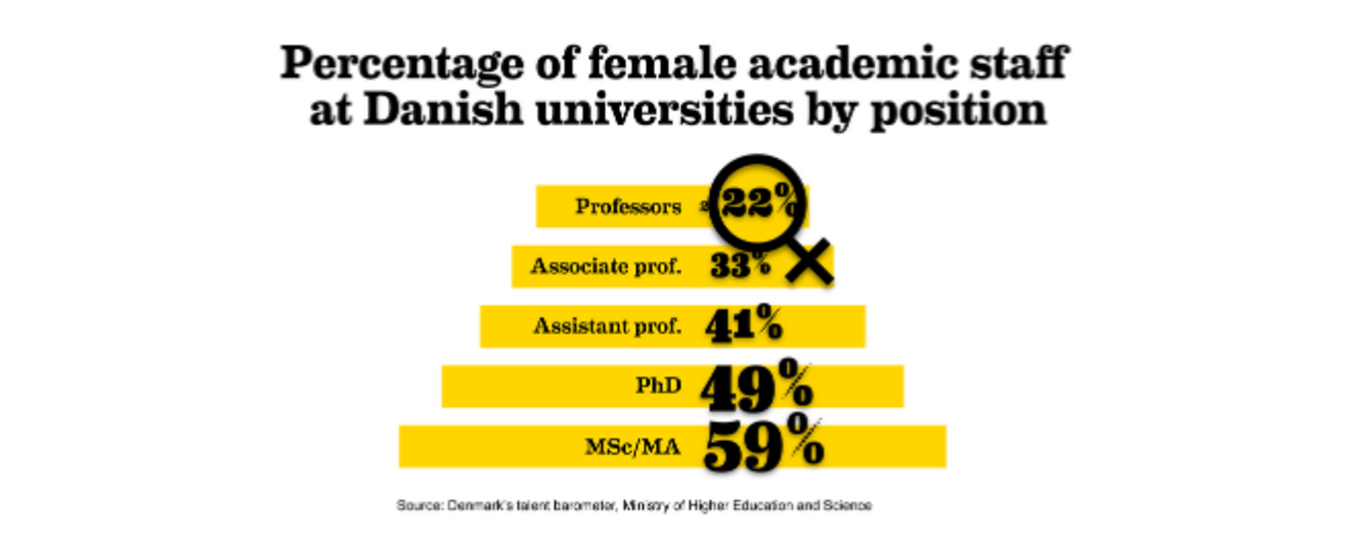

In December, Minister for Higher Education and Science Ane Halsboe-Jørgensen (Social Democrats) unveiled the Inge Lehmann programme, a new talent programme that’s intended to help create better gender balance in Danish research. A balance that’s particularly off at professor level: in Denmark, just under one in four full professors is a woman.

But the problem is complex and can’t be solved by talent programmes in isolation, contends Evanthia K. Schmidt, associate professor and director of the Danish Centre for Studies in Research and Research Policy and an expert on gender equality in academia.

The Inge Lehmann programme will award 20 million kroner in grants annually. By comparison, a similar programme from 2015, the YDUN programme, awarded 110 million kroner annually. That programme received 553 applications, and grants were awarded to 17 projects – a success rate of just 3 percent.

“If these women had applied to the general research council programmes instead, the success rate would have been 13 percent,” says Schmidt.

Is the programme irrelevant?

“Not for the few women who get grants. But it’s a symbolic gesture, and the programme won’t change anything in the big picture,” Schmidt says.

Shift focus from the individual female researcher

According to Schmidt, programmes like the Inge Lehmann programme and YDUN are founded on the assumption that the gender equality problem can be solved at the level of the individual.

“But I’d like to argue that we need to shift our focus from the individual female researcher to the institutional and systemic level. In other words, to the reasons why women get fewer grants and professorships. And university management and research funding organisations have a responsibility to prioritise this issue in practice,” she adds.

She also notes that the goal of better gender balance at AU has been included in AU’s new strategy for 2020-2025 – a first.

“This is very positive. When it’s in the strategy, it’s binding, and as a university, we have an obligation to take action to reach the goal. It’s the first step.”

According to Schmidt, the next step for AU will be when AU’s diversity and equality committee presents its draft action plan for greater diversity at AU. The major points of the action plan will be presented at a workshop on March 13.

“If the senior management team and the Committee for Diversity and Gender Equality direct the departments and schools to find concrete solutions in the new action plan, the individual departments and schools will make much stronger efforts to improve gender balance,” Schmidt says.

Denmark is falling behind

While politicians in Denmark nudge their universities with measures like think tanks, commissions and talent programmes, politicians in Norway and Sweden have taken their gloves off: these countries have passed legislation imposing gender quotas, earmarked positions for women and financing long-term national initiatives.

In her research, Schmidt has studies the different approaches to the problem in the Scandinavian countries. She cites a variety of examples of long-term initiatives introduced in the countries with which Denmark normally compares itself, such as the Research Council of Norway’s requirement that women make up 40 percent of the center directors applying for grants from the programme ‘Sentre for fremragende forskning’ (centers for outstanding research).

“This is something that motivates the institutions to look at gender balance at center director level,” Schmidt says.

“In Great Britain, you have ‘the Athena SWAN Charter’. This is a comprehensive programme that aims to create incentives for the universities to address barriers to gender equality. The institutions that are involved in the programme pledge to respect a number of principles when implementing long-term action plans. They are awarded gold, silver or bronze awards in recognition of their efforts. An additional requirement for health sciences institutions is that they must earn at least silver to be eligible to apply for competitive funding from the state,” she explains.

Denmark is a meritocracy – but meritocracy has its limits

Whereas there’s widespread acknowledgement of gender inequality in academia in Norway, Sweden and Great Britain, in Denmark, there’s a tendency to believe that academia is a functioning meritocracy where men and women have equal opportunities. In other words, Danes tend to believe that researchers’ applications are judged solely on their merits.

“But meritocracy has its limits. Because talent is a subjective concept. We have to attempt to identify the cultural and structural biasses that pose barriers to equal opportunity for all in academia,” Schmidt says.

Greater diversity equals greater innovation

Schmidt makes it clear why it’s important to prioritize greater equality in academia:

“It’s not just for women’s sake. And it’s not just to ensure that there’s a level playing field for all talents. It’s about the contents of the research,” she says. Because diversity among researchers leads to more diversity in research, she explains:

“Because men and women prioritize different research areas and methods, and teams with greater diversity are more innovative. We have to mobilize all of our resources to address the major challenges facing society effectively.”

The Inge Lehmann programme

- The purpose of the programme programme is to promote talent development in Danish research by fostering a higher degree of gender equality in academia in Denmark.

- The Inge Lehmann programme will award 20 million kroner in grants annually.

- Researchers from all fields – men and women – are eligible to apply for funding from the programme. Female applicants can take priority over male applicants in cases in which both are equally qualified.

- The programme is names after the woman seismologist and state geodesist Inge Lehmann, who demonstrated that Earth has a solid inner core in 1936.