Quality Tweet

Lone Koefoed Hansen, associate professor at the Department of Aesthetics and Communication, Digital Design; and Peter Lauritsen, associate professor at the Department of Aesthetics and Communication, Information Studies. Founders of the '(Alternative) Committee for quality and relevance in higher education.'

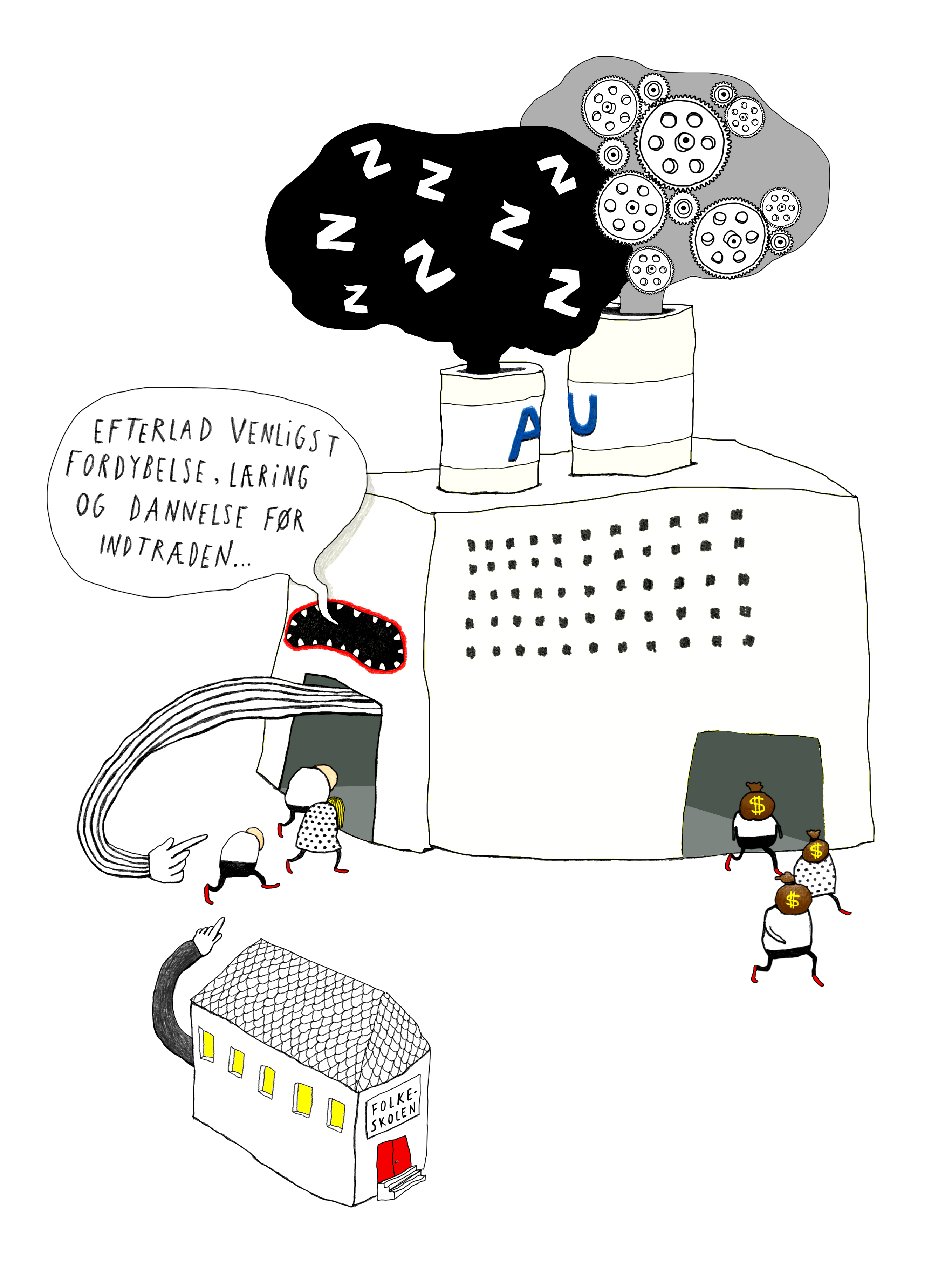

On 30 October Morten Østergaard, the Danish Minister for Science, Innovation and Higher Education, set up the “The alternative Committee for quality and relevance in higher education”. The aim is “to provide concrete recommendations”, and it’s all about converting education into employment and growth. The members of the committee come from a narrow circle – the majority of them being economists – and there is some concern that a lot of relevant perspectives will not be included in its work.

So on 31 October we set up the “(Alternative) Committee for quality and relevance in higher education”, which also aims to provide concrete recommendations about how to improve the quality of higher education. Our committee is open to everyone who’s on Twitter, and this is where there’s a wide-ranging debate about what quality is, where the problems are to be found, and what can be done about them. There have been about 650 comments so far, revealing that quality means different things to different people, and that the responsibility for lack of quality cannot be attributed to any one particular source. Here are some of the problems that have been mentioned in the debate:

In terms of education structure, young people are trained to focus on their targets even while they’re still at school. They’re expected to complete their education quickly so they can start being useful to society as soon as possible. Speed and financial utility are equated with quality, whereas in-depth study, learning and education are not part of the structural quality perspective.

University managements translate demands for increased quality into measurable parameters such as the number of lessons, results of evaluations, or the number of students passing exams – instead of constructively involving themselves in the very different environments for learning that are created by students and teachers.

Teachers don’t regard teaching as a space for academic development, and they don’t discuss this with their colleagues in anything other than anecdotal form. They do not make informed educational choices about how students should administer their 27.5 hours per ECTS credit, but simply put more texts on their curriculum and talk a little faster in their lectures.

Students regard the university as a shop in which motivation and academic inquisitiveness are the responsibility of the teacher or degree programme in question, believing that it’s perfectly legitimate to refrain from preparing for your lessons if you have to go to work or don’t think the course concerned is interesting enough.

The discussion shows that boosting quality is a complex task which can’t be performed by the people involved standing in separate corners of the ring and criticising everyone else. Perhaps the teachers are right to complain that students these days belong to a generation who have had things far too easy; but the teachers must surely accept some responsibility if their students fail to prepare for lessons and aren’t particularly interested in the teaching. Nor is it any good if the students demand more lessons without considering what they can do themselves to improve their learning process, and without wondering whether more lessons will actually improve quality.

Quality is a complex concept, so it’s not enough to simply react with anger to other people’s proposals and ideas. You also have to develop your own visions and ideas about what you can do yourself to help give quality the boost it needs. In this process we can all start by saying aloud what we and everyone else can do to improve things. But also by talking about what we’re already doing so well that other people could learn from us. Some of this work has already started in the self-appointed committee on Twitter. It’s all about broadening the scope of the discussion so it covers all levels at AU.

Follow the debate

#AltUdvalg is hash-tagged on Twitter.

This is our mandate - and where our conclusions will be posted

Translated by Nicholas Wrigley