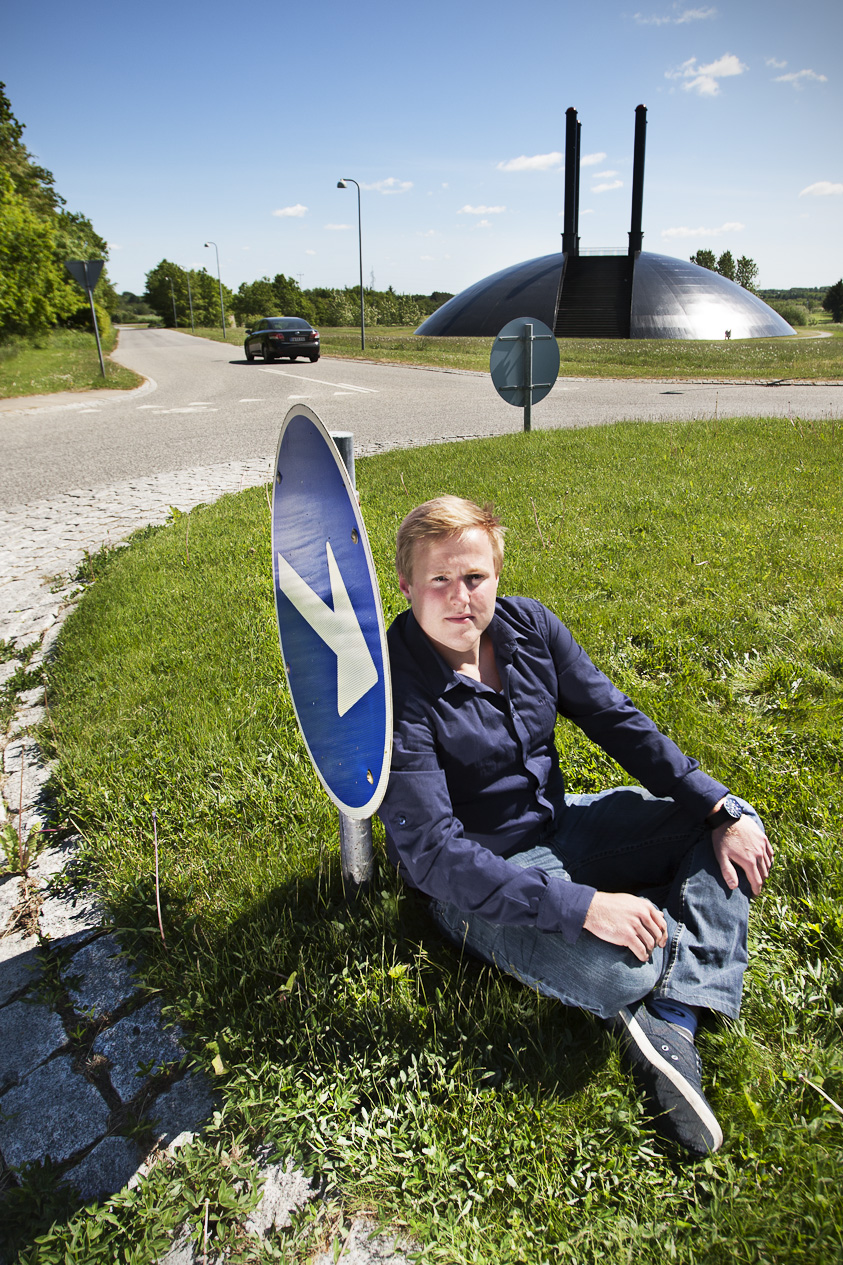

Try visiting Herning, Østergaard

Morten Østergaard, the Danish Minister for Science, Innovation and Higher Education, criticised the universities recently for focusing too little on the private labour market. But the criticism is like water off a duck’s back at AU Herning, where 80% of the graduates find jobs in the private sector. The minister is more than welcome to visit Herning to see the success story with his own eyes.

Two days a week Kasper Skou Andersen (an MSc student of Engineering) and Christian Ebbesen (an MSc student of Business Administration) abandon their lectures and class teaching at AU Herning to work without pay in the private sector. They have both opted to use a mentor company scheme which has been run by AU Herning on their degree programmes for a number of years. The scheme involves connecting students with a company where they work for one or two days a week, giving them the chance to test theory in practice on a regular basis. They both agree that the scheme is a good one.

“Let’s face it, there’s a limit to how much you can learn from reading books. This scheme enables you to learn a theory and test it in practice, giving you an effective practical framework for the learning process,” says Christian Ebbesen, who works at a firm of consultants called Innohow which was actually started by a former AU Herning student.

“It also gives you some great discussions in class because each of us has something to report from the companies we’re linked up with,” adds Kasper Skou Andersen, whose mentor scheme involves working at Zystm A/S, a company that supplies design and logistics systems for hospitals and laboratories.

Graduates grabbed by private sector

The two students hope that the experience they gain from the scheme during their degree programmes will make it easier to get jobs, and departmental statistics show that they have a good chance of success.

“80 per cent of our students get jobs in the private sector,” explains head of department Michael Goodsite. The secret behind this particular statistic is that the department attaches very high priority to contact with the business community – in particular the local business community.

“All our students have some kind of contact with private businesses during their degree programme,” says Goodsite.

And this is why Morten Østergaard’s criticism is lost on him.

“What we have is the opposite problem. Private companies grab most of our students as soon as they graduate, which makes it harder for public-sector employers to get the graduates they need,” reports Goodsite.

Close partnership with local business

The mentor company scheme is just one of the ways in which students at AU Herning can gain contact with private companies during their degree programmes. Placement periods are another option, and the students are also encouraged to use companies as cases in their assignments. AU Herning also works with the municipalities to arrange long-term development processes in businesses based on strategic areas of focus.

The business community is supporting these bridge-building efforts – including financial support. The mentor company scheme receives funding from five municipalities, the Mid-Jutland Region and the Business Development Centre Herning & Ikast-Brande, explains Anna Katrine Bruun, who is a senior consultant for knowledge exchange.

“We definitely feel that it’s our job to help create knowledge and growth in local companies. This area of Denmark isn’t blessed with many universities, and it is sometimes difficult to persuade graduates from Aarhus to move to Ringkøbing. We need to start building bridges before our students graduate, and we can see that it works.”

One model for everyone?

“If Morten Østergaard wants to take a look at what we’re doing here, he’s welcome to pay us a visit. And any other interested parties are welcome, too,” promises Anna Katrine Bruun.

But can AU Herning’s success in building bridges between private companies and the department be copied by other departments and institutions of education? Perhaps, says Michael Goodsite. If it makes sense to do so.

“We’re part of a School of Business and Social Sciences, so it makes sense to do this kind of thing here. But close contact with the business community might not be relevant for other departments.”

And this is his point in a nutshell, and the reason for his criticism of Morten Østergaard’s words. In the world of universities, one size does not fit all.

Old-fashioned attitudes

Anna Katrine Bruun feels that old-fashioned attitudes still prevail in some areas of our universities, where excessive interaction with the private sector is still frowned upon by some.

“We’re a challenge to such attitudes. But we don’t compromise on our academic demands. We just add motivation,” she says.

Both Kasper Skou Andersen and Christian Ebbesen feel that they have learnt more than they could have learnt from books.

“I’ve gained more professional self-confidence because I’ve grown used to dealing with clients and talking to managers. I’m using this at the moment in my Master’s thesis, which involves interviewing a range of departmental managers,” explains Christian Ebbesen. And he continues:

“I’ve been involved in all kinds of projects, including helping to define the company’s strategy and designing our product catalogue.”

Kasper Skou Andersen hasn’t been hiding behind a desk in a company, either.

“A normal week might include dealing with a specific issue, screening it, considering the alternatives and recommending potential solutions to the management,” he reports.

But interaction between companies and the world of education can sometimes lead to dilemmas for the students, he explains.

“Your mentor company wants concrete input and attaches less importance to theory; while your department focuses on theory and is less interested in what your company might get out of it. So satisfying both groups of stakeholders is not always easy – you don’t want to disappoint either of them because they both have a big influence on your future.”

Is Morten Østergaard right?

Could our universities be better at training graduates for the private labour market – or is his criticism way out of line?

Let us know what you think - you can add a comment below, or join the debate Give us your views.