More students than usual failed the final exam on their dentistry degree – students think they’ve been treated badly

Students have criticised the exam procedure in the final semester of their dentistry degree after the failure rate surged. Students who failed missed their graduation, had to wait for their dentistry license, and feel misjudged. The director of studies emphasises that the examiners and co-examiners are highly qualified and focuses instead on the level of student effort.

After the summer exams, 11 students on the dentistry Master’s programme were astonished to find out that they’d failed the dental prosthetics exam in the final semester of their degree – and that, as a result, they could not get their license to practise dentistry or graduate with the rest of their year group.

The exam is known for being one that everybody passes, and when they left the exam room, they had the feeling that everything had gone well. Compared with failure rates over recent years, this year’s figure stands out. Last year, between one and five students failed – if fewer than five students fail, the degree programme does not disclose the exact number for reasons of confidentiality. And, in 2022 and 2021, no students failed the dental prosthetics course.

One of the students who failed this year is Asta Barkmann, who describes the whole process as “surreal”.

“I left the room thinking: ‘That went well. I’m on top of that’. And then I failed, so now I’m left wondering what happened,” says Asta Barkmann.

Number of students who failed the dental prosthetics exam between 2020 and 2024.

2020: 1-5 (exact figure withheld for reasons of confidentiality)

2021: 0

2022: 0

2023: 1-5 (exact figure withheld for reasons of confidentiality)

2024: 14

Note that three students failed the re-examination in 2024, which brings the total number who failed this year up to 14.

Source: Health Studies Administration

It’s not the failing itself that she describes as surreal, but rather what happened afterwards, she explains. The teachers and the director of studies invited the students to a meeting before the re-examination, explains Asta Barkmann, so that they could ask questions and prepare to take the exam again.

“We wanted to see concrete examples of what we’d done wrong. We compared our answers with some of the few students who scored 12, and we couldn’t see what the difference was. What they said in the meeting didn’t really make sense, and we felt like the teachers were simply reprimanding us for not being able to understand the questions. One of the teachers lost it. People began to cry,” says Asta Barkmann.

The students who failed requested access rights to the examiner’s and co-examiner’s notes to help them understand their assessment. But they were told that the examiner hadn’t made any notes, and that the co-examiner had simply written a zero and an upwards arrow. Several students have complained about the exam assessment, but a complaint takes about two months to process, and this doesn’t even include July.

Students: We’ve been assessed harshly

Another student who failed is Howraz Mohammad. He is equally puzzled by the exam procedure.

“It’s not the toughest exam, and the subject itself is not difficult. We have looked at what is required for a 2, and our exam papers definitely meet this requirement. We have been assessed harshly,” he says.

Both students point out that the exam questions were difficult to understand. Howraz Mohammad explains that the questions were worded confusingly, which made it difficult to know what the teacher expected.

“In one of the questions, you couldn’t work out whether the answer should be in the singular or the plural. The question was: ‘What relevant question(s) would you ask the patient?’ (ed: In Danish, the question was: Hvilket relevante spørgsmål, ville du stille patienten? Here, the hvilket (‘which’) indicates singular and the relevante (‘relevant’) indicates plural). So people were confused about the words ‘which’ and ‘relevant’. Were we being asked for one or more than one question? Many of us went with plural and gave examples of more than one question,” says Howraz Mohammad.

Asta Barkmann mentions another example:

“In one of the questions, we were asked to explain (ed: in Danish, redegøre) our diagnosis of a particular tooth. We were all agreed that the tooth had to come out. But when it says ‘explain’, you think that you need to account for this in some way. In other words, explain why the tooth should be extracted. We got 0 for this question, and we were told at the meeting that this was because we weren’t allowed to write more than one line. We also got 0 for the subsequent sub-questions, the assumption being that, if you can’t answer the main part of the question correctly, you can’t get the rest right either,” she says.

At the meeting before the re-examination, Howraz Mohammad had hoped that the teachers would listen to their objections. Instead, he believes they were trying to defend themselves.

“The meeting wasn’t useful at all. We hoped to find out what we needed to do to pass, and we tried to explain to them that some of the questions could be misunderstood. But it was as if they were trying to defend themselves. The teachers and the director of studies thought we should trust them that things were being done properly, but we were given no explanation of why we got the grades we did,” he says.

Students couldn’t get hold of book

Asta Barkmann explains that, before the exam, there were rumours that “more people would fail this year because the teachers didn’t think we were taking it seriously enough.”

“That was also the tone I picked up on when I asked about things in the syllabus during the meeting. There was one book on the reading list that I couldn’t get hold of because it was sold out at the publishers, and I mentioned this at the meeting. Then they began to reprimand me, and they said it was a clear example of the fact that none of the students on this course read the books or took the subject seriously. But we work really hard on this degree programme,” says Asta Barkmann, who emphasises that most of the students do in fact read the books.

But can you understand them when they criticise you for not having one of the books on the syllabus?

“Yes, I can. But I just needed to know how to get hold of the book, which was not available anywhere. I am responsible for my own education, and I know that. They suggested we read another, very expensive book instead – but only certain sections. So I asked which pages were relevant. But they didn’t tell us, because they said that, at our stage of education, we should know which pages were relevant,” she says.

Howraz Mohammad acknowledges that the dental prosthetics course had a reputation for being easy to pass.

“Perhaps some students took it less seriously than the other courses. There was definitely a sense that you didn’t need to fear dental prosthetics, but I have no idea what the teachers are thinking,” he says and explains that the subject also contains a clinical exam, which he passed without difficulty – as did Asta Barkmann.

Couldn’t look for a job or graduate

Because he failed his final exam, Howraz Mohammad had to put his job search on hold over the summer months. This is the time of year when most dentistry students find a job, because they expect to be qualified to practise from August.

“It has been extremely frustrating. I stopped looking for jobs, because I didn’t think it made sense to apply without my certificate. I went for interviews, but I had to let them know afterwards that I had failed my exam. I know that some of the other students who failed had already been offered jobs before the exam,” he says.

The two students also had to miss their graduation.

“We received an email saying that we were of course welcome to attend the ceremony this year but that our names would not be read out. Or that we could go to the 2025 ceremony instead. Then we’d have to sit there and have it rubbed in our face,” says Asta Barkmann, who continues:

“Last year, one person failed the course and attended the graduation ceremony, but this person was photoshopped out of the group picture that was taken of the year group. None of us wanted that to happen to us,” she says.

Director of studies: It’s our responsibility to ensure students live up to the academic regulations

The director of studies on the dentistry Master’s programme, Irene Dige, acknowledges that the failure rate is higher in dental prosthetics this year and describes the situation as incredibly frustrating for the students. She agrees that the exam results must have come as a shock to them.

She can only speculate as to why the failure rate is higher this year, but she explains that it’s not uncommon for subjects that nobody usually fails to suddenly have a high failure rate, because students get the false impression that the exam is easy. But she has also come across things that have surprised her in this whole process.

“I was surprised to hear that students didn’t have the books that were recommended. Apparently it was difficult to obtain one of the books. It’s a shame we only found out about this after the exam, because there are alternative books and we could have helped them. I also understand that only half the students turned up to the Q&A meeting that was scheduled before the original exam. The teachers were surprised by this lack of attendance,” says Irene Dige.

Even though she admits the failure rate is high, she doesn’t think that failing in itself is unjustified.

“The dentistry programme is a professional degree, and this means that, as soon as students have their certificate, they can go out and treat patients. If they don’t perform well enough in their exams, we cannot vouch for them. It’s our responsibility to make sure they live up to the academic regulations. The exams are anonymous, so the students’ exam grades have nothing to do with whether the examiner likes them or how well they’ve performed in class,” says Irene Dige.

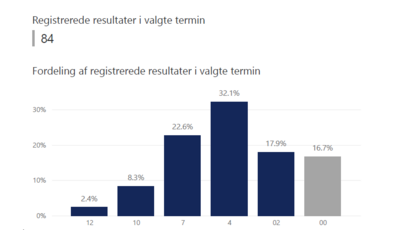

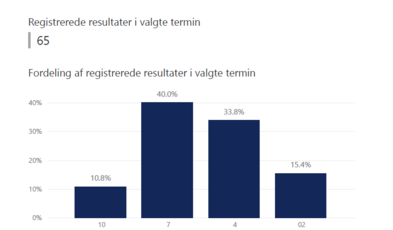

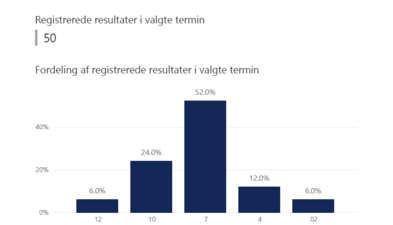

Declining average grade

She notes that students’ average grades for dental prosthetics have also fallen in recent years. In 2021, when nobody failed, twelve per cent of students got a 4 and six per cent got a 2. In 2022, when again nobody failed, 34 per cent got a 4 and 15 per cent got a 2.

“I can understand that some people might think the exam has got more difficult. But the level has not changed. It has the same academic objectives and the same teachers,” says Irene Dige.

While the students themselves may not be able to tell the difference between those who scored 0 and those who scored 12, it’s essential they trust the examiner and co-examiner, says the director of studies.

“They are academic staff with many years of experience in both teaching and exam assessment,” she says.

Director of studies: Students can always contact us with questions

Irene Dige is keen to point out that she cannot comment on specific questions because she has not seen them, but she emphasises that students can always contact an examiner during an exam if they are unsure of the wording of a question.

“Nobody raised this issue during the exam, and after five years of studying here, they know that this is an option open to them. We are on the other end of the phone if anything is unclear.

The director of studies also believes that the examiners gave students the benefit of the doubt when it appeared that they may have misunderstood the intention of the question. Still, there are certain standards that have to be met, she stresses.

“It’s an exam at a higher taxonomic level and students need to answer the questions being asked, and nothing else. If students write something irrelevant to the question, it can drag down their mark, because it shows they haven’t understood the essence of the question,” she says.

Students are frustrated

When asked about the Q&A meeting before the re-exam, which several students found uncomfortable and pointless, Irene Dige explains that the purpose of the meeting was to prepare them for the re-exam – not to review the failed exam. She acknowledges that many students were upset at the meeting.

“I could see that the students were very frustrated, and it seemed as if they were more interested in knowing why they had failed than in getting ready for the re-examination. In this way, we probably expected different things from the meeting. But I certainly didn’t see anybody reprimand the students. Nor did anybody raise their voice. Several students were upset, and that wasn’t a pleasant experience for anyone – it’s never nice to see anyone upset,” says Irene Dige.

Degree programme is updating its procedures

Asta Barkmann was surprised that there were no examiner’s notes to see, and that the co-examiner had only written an 0 and some arrows next to her name. This incident has prompted Health Studies Administration to update its procedures.

“I’ve been the director of studies for five years, and this is the first time that students have asked to access their assessments. So, in collaboration with Health Studies Administration, we are now working to ensure a good procedure going forward. Health Studies Administration have updated their website for co-examiners and tightened up their communication with them, for example by linking to the Examination Order, and I have ensured that all members of teaching staff know the rules. It is of course regrettable if insufficient notes were taken in this case,” says Irene Dige.

But the director of studies points out that the notes are not intended for the students.

“The notes need to make sense for the examiners, not the students. Examiners take notes in case there is a complaint. But these notes don’t have to be understood by everyone. It is the co-examiner who determines the form of the notes. It could be a number, an underlining, or something entirely different,” says Irene Dige.

There isn’t much that can be done about the length of time it takes to process a complaint, she explains.

“It goes to the lawyers, who send it out to the co-examiner and the examiner, who then send it back to the lawyers, and so on. Unfortunately, it takes a long time to process cases like this,” says Irene Dige.

When asked whether the case will give rise to changes in the programme, Irene Dige answers:

“We always look at courses with high failure rates to see if something needs to be done differently. I think the teachers on this course will make a concerted effort next year to prepare the students for the exam and to emphasise the standard they expect,” she says.

Three failed the re-examination

Asta Barkmann passed the re-examination in August and has now received her authorisation to practise as a dentist. Three students failed the re-exam and will now be given a third attempt. The students who complained received a response September. None of them was successful. Omnibus does not know whether Howraz Mohammad passed the re-examination.

Translated by Sarah Louise Jennings.