Multi-million kroner grant will make 50,000 dried plants and seeds from all over the world accessible to all online

A DKK 30 million grant from the Ministry of Higher Education and Science will fund the digitisation of Denmark’s natural history collections. At the Science Museums, about 500,000 herbarium specimen sheets will be digitised over the next five years. We spoke to the vice-dean at Tech about the project.

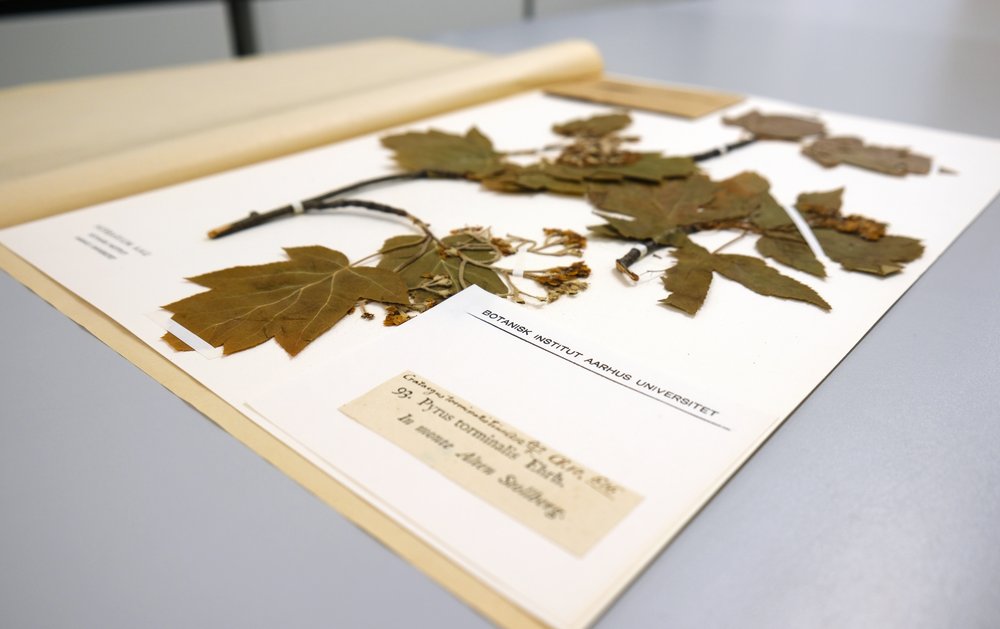

The Aarhus University Herbarium in the University Park is packed with light grey metal shelving units where between 500,000 and 750,000 brown herbarium sheets are stored. Plant specimens gathered for research purposes are mounted on every single sheet. A single specimen and a tiny label are mounted on each sheet. The labels identify the species of the plant, where it was collected and the name of the collector.

Since 1963, the herbarium has housed Aarhus University’s collection of dried plants and seeds from the entire world – collected over two hundred years. Until now, only researchers have had access to the wonders of the collection. But now it will be made accessible online for plant lovers everywhere.

MORE ON THIS STORY: The herbarium at Aarhus University houses 750,000 plants from all over the world, spread across three floors – and new specimens are added each week

This is being made possible by a 30-million kroner grant from the Ministry of Higher Education and Science research infrastructure pool to finance the digitisation of Denmark’s natural history collections. This includes the Science Museums, which the Herbarium is part of.

“A dream we’ve had for 15 years is now coming true. We’ve been working with digitising data since the 1990s, and now we’ll be able to conclude the process and get everything digitised,” said Fin Borchsenius, who is vice-dean of the Faculty of Technical Sciences at AU. As a former research director of the Herbarium, he was involved in earlier digitisation projects, so he’ll also be a member of the steering committee for the next phase of the process.

Part of a European project

The multi-million kroner grant is part of the EU research infrastructure System of Scientific Collections (DiSSCo) project, a collaboration that so far includes 120 institutions in 21 countries. The goal of the project is the digital unification of all European natural science assets.

Sixty-one million kroner have been allocated to the digitisation of the Danish natural science collections. In addition to the DiSSCo grant from the Ministry of Higher Education and Science, the remainder of the funding for the project comes from the participating museums as well as the Technical University of Denmark in Lyngby, which will scan the museum collections.

The grant is a total budget for the development of infrastructure and will not be distributed among the museums. According to Borchsenius, this means that the grant should be viewed as a national investment.

500,000 specimens

Borchsenius and his colleagues began building databases of digitised plant specimens as far back as the 1980s. And about 150,000 of the herbarium’s plant speciments are accessible online today.

“And then there are about 500,000 specimens that haven’t been digitised because they’re older. These are what the new infrastructure will allow us to have digitised,” Borchsenius explained.

The advantage of digitising natural history assets is that it allows researchers and students all over the world to access enormous databases containing these collections. To take just one example, this material can be used in connection with analyses of biodiversity, Borchsenius said.

A fully automated process

Until now, digitisation has been a partially manual process: all data has been entered manually. But the grant will finance new infrastructure so that scanners will be able to handle the entire process.

“In Holland, they’re already starting to build an assembly line that can automate the process. So it can be done a lot faster than before, Borchsenius said, adding:

“Herbarium collections have the advantage of having a flat format. So they can be fed into a machine that uses recognition tool to scan them. It then takes a photo and scans the label. All the data will be linked to a barcode – and then the specimen has been digitised.”

Where the scanners will be located in Denmark hasn’t been decided yet. However, this doesn’t concern Borchsenius:

“The worst-case scenario is that we will have to send our herbarium collections in a truck to Glostrup, where the University of Copenhagen’s botanical collection is located. At the end of the day, that’s better than sending the herbarium sheets around the world.”

The challenge will be the zoological collections

While geography is no problem, the diversity of the collections presents the real challenge.

“It’s a fairly well-tested technology that’s straightforward when it comes to plants. But there can be challenges, for example how to scan a large collection of flies or other zoological collections, where insects are mounted on pins accompanied by a tiny cardboard sign with information. So that’s why DTU is involved in relation to developing scanning methods that can handle this,” Borchsenius said.

Although the plants are relatively simple to scan, som labels are handwritten and so old that they have to be processed by specialised scanners.

“For example, this might be specimens from amateur plant collections that people have lying around in their attics. They’re often found when someone dies, and then the collections are often donated to us. Some of them can be quite old, but we archive them, because they often show what kinds of plants used to grow in places where there might not be any nature left,” he said.

Despite the diversity of the collections, Borchsenius believes that the over 500,000 specimens will all be successfully digitised in the near future.

“The plan is that we can manage it within five years,” he said, adding:

“The timing is really good right now, because the technology is advanced, and that makes it possible to develop a digital infrastructure.”

Translated by Lenore Messick