FROM DEPUTY JUDGE TO PHD STUDENT: "I STILL WANT TO PURSUE MY CAREER, BUT IT CAN WAIT A LITTLE BIT”

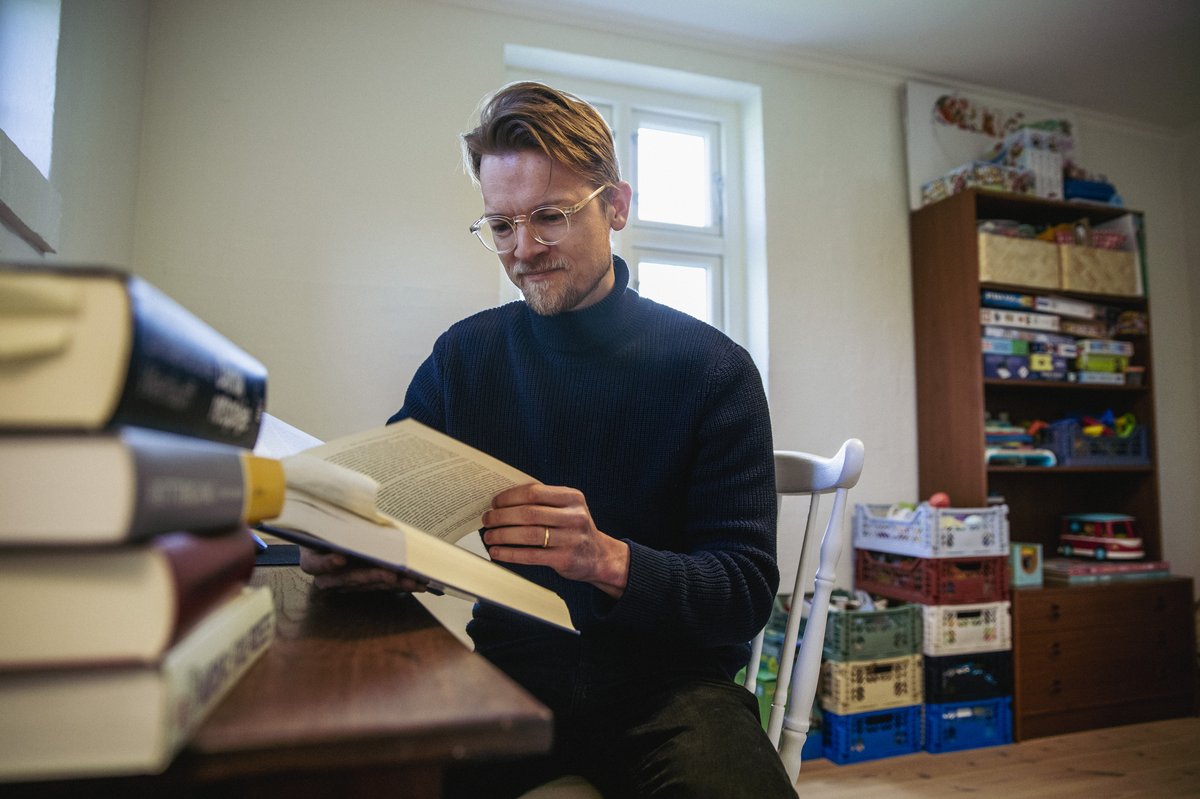

Simon Kærslund Terp’s positions as deputy judge in Aalborg and senior consultant on the SKAT inquiry commission meant he was well on his way to becoming a High Court judge. But then his two children were born, and with that came a desire to spend time with them while they were young. The solution? A PhD project.

SERIES: FROM A TO PHD

This article is part of a new Omnibus series that explores the many paths to a PhD – and not least the hopes and dreams of grad students about the future that awaits them on the other side.

Would you like us to tell your story too? Or know someone else who’d be interested in sharing their story with us? Write to us at omnibus@au.dk.

Tall spruce, beech and oak trees tower over the winding landscape of Central Jutland. Quite a few trees, actually. Up here, about a 40-minute drive outside Aarhus, you can really feel that spring has arrived. The morning sun reflects off the newly sprung and dewy leaves on the branches, and the scent is unmistakable: the fruit trees are in bloom. Thirty-six-year-old PhD student Simon Kærlsund Terp and his family call this lush and green area home. He has lured Omnibus out of the big city with the argument that this location is closely interwoven with his path to his PhD at the Department of Law.

Whenever possible, this is where he likes to work on his legal research, with a view of the many garden projects that are gradually taking shape. He and his wife both have green fingers and they have been planting flowers and trees galore since they bought the house:

"I might as well have been a biologist," he laughs and continues: "I actually considered journalism as well. I can’t with 100 per cent certainty say why I ended up choosing law. It was a coin toss - of a three-sided coin.”

The coin flip landed in law's favour, and during his studies he quickly found out that he was really good at it. The dream of a career as a High Court judge took root, and he is well on his way with a number of important positions under his belt, including deputy judge at the court in Aalborg and as senior consultant in the highly publicised commission of inquiry into SKAT. But then he pushed the pause button and applied for a PhD:

"We had our first son, Valdemar. And like so many others, my priorities completely shifted. It suddenly became less important that my career trajectory maintain a constant upwards motion,” he explains.

A CRAVING FOR MORE FLEXIBILITY

Being a deputy judge is not one of the most flexible jobs in the world, explains Simon Kærslund Terp. The hours quickly added up during a normal working week full of criminal, bailiff and probate cases. And since the job was located in Aalborg, the hours of the day were quickly depleted. So he decided to find a different job and was offered the unique opportunity of working for the inquiry commission into SKAT. The working week became a little bit more flexible when he worked for the commission.

However, when the specific task he was working on for the commission came to an end, he had to consider his next step once again. Returning to work as a deputy judge was the obvious choice. However, his second child, Maja, had just made her appearance.

A myriad of thoughts and ideas on how to resolve this swirled in his head, and after careful consideration, he realised that a PhD might be the perfect solution.

"In a PhD programme, you can take a day off if your child is sick. If you’re a deputy judge and you have a criminal case, you call your secretary, who then says: Oh no! Because she then has to call the defence lawyer, the prosecutor, the police, three witnesses and the defendant to let them know everything is cancelled. It's a long domino effect of problems," says Simon Kærslund Terp.

Although the possibility of more time and increased flexibility was at the forefront of his mind, his career also played into the decision. He viewed the PhD as a chance to solve a very specific challenge of the courts, namely the complex issue of the right to appear locus standi in court cases.

A THOUGHTFUL PHD PROJECT FOR A THOUGHTFUL PHD STUDENT

In short, locus standi means that the plaintiff must have a credible interest in having a case heard by the courts:

“For example, if you see two cyclists crash into each other and you think: Wow, that was clearly the fault of one of the cyclists, and they should definitely compensate the other cyclist. You won’t be able to do that because you have no locus standi in the matter. The two cyclists have to sort that out themselves," he explains.

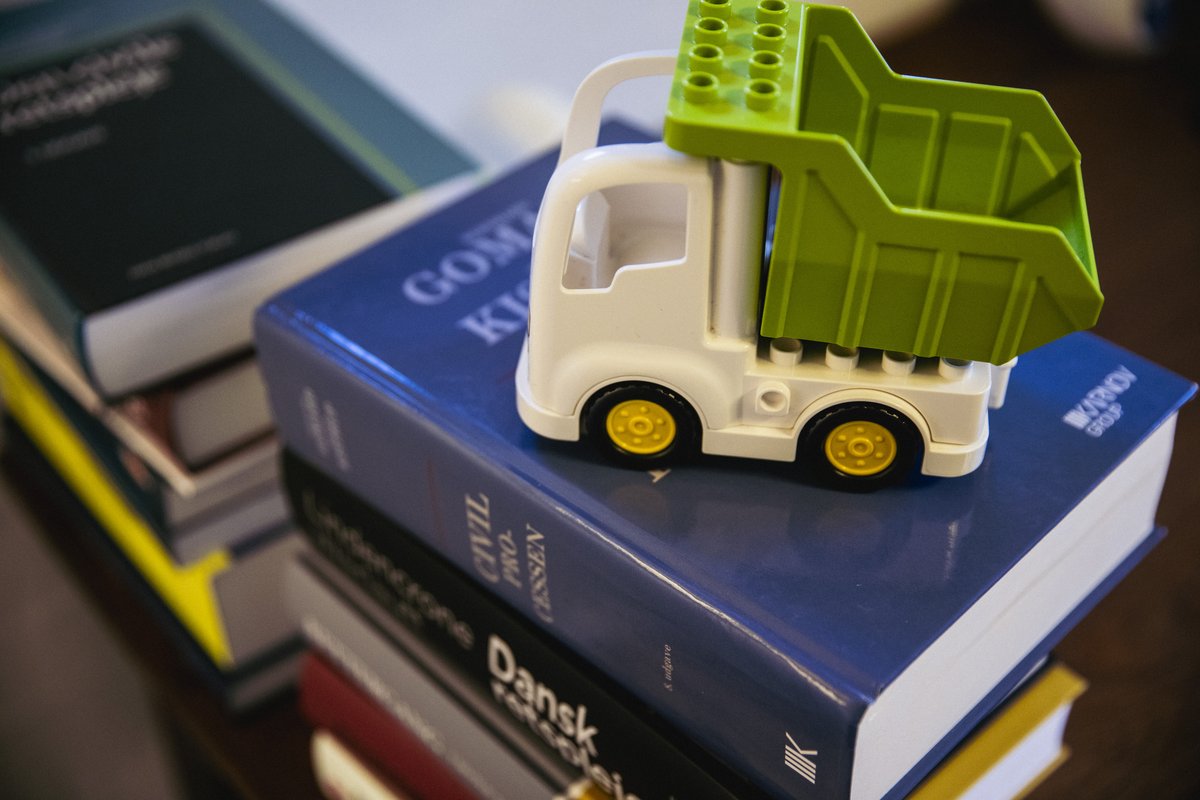

However, obvious cases like the cyclist case Simon Kærslund Terp outlined above are the exception rather than the rule. Most cases are a lot more complex, he says. In general, the concept of locus standi is described in very different ways and often in very general terms in textbooks. There are no applicable laws and rules on how to determine it, so the rules on locus standi are instead created by the courts through individual court rulings. The concept therefore needs to be thoroughly systematised, and doing so is so extensive that it would require a PhD student with the courage to sit down and go through case after case after case. Simon Kærslund Terp was keen on taking on the task:

"The first thing I did was to go through what has now grown to 1,200 rulings, and try to systematise them in order to see: What kind of system do we end up with? And does it actually give us some rules that are more applicable than the broad descriptions in textbooks? That’s essentially what the project is about."

Some might think that such a towering stack of rulings would be so dry that it could spontaneously combust. But not for Simon Kærslund Terp. He describes himself as a thoughtful and sometimes introverted person who can spend hours trying to solve complicated legal knots while walking around his acres of land, pulling up weeds.

"And it's crazy because I'm not very good at maths. So logical deduction doesn’t come naturally to me, but when it comes to words, sentences and their context, then something just clicks into place for me.”

He began his PhD project in 2021, but it will take another year for it to be ready. The PhD has had to give way to both parental leave and a leave of absence to finalise his work for the inquiry commission. He hopes that the dissertation will be actively used by both judges and lawyers and not just end up in a drawer:

"If you’re a judge or lawyer and you have a case where you're in doubt about whether the plaintiff has locus standi, I hope you will be able take my book off the shelf and relatively quickly find the answer to your question."

"IT’S OKAY TO SLOW DOWN "

The whole process of slowing down his career in favour of spending time with his family has made Simon Kærslund Terp realise how he wants to combine work and leisure going forward:

"In the past, I was probably more interested in climbing the ladder as quickly as possible. I was very career-conscious in the beginning. I had to do the right things at the right times. There’s been a shift along the way. I still want to pursue my career, but it’s okay to slow down a little bit. It doesn't all have to happen in my 30s. And I'm lucky enough that you can't be appointed a judge until you're relatively old."

This is also why it makes sense that he and his wife chose to buy a house in the middle of nowhere:

"This house costs less than half of what a house costs in Højbjerg. So we're already saving a huge amount of money. It's a kind of trade-off. There are so many great things about a PhD. Good colleagues, exciting work, career opportunities afterwards, etc. The only negative thing is perhaps the salary. I’ve had to swallow that in order to enjoy all the other benefits. And that’s okay."

WHAT NOW?

But how does Simon Kærslund Terp see the future? Does he go straight back to his job as a deputy judge, or has the flexibility of academic life tempted him to stay in academia a little longer?

"I don't think I can let go of the flexibility just yet because my children are still so young. But when they get a little older, flexibility might become less important to me. But it’s still really important at the moment, so I hope to become an assistant professor at AU afterwards."

The dream of becoming a High Court judge is still alive and well, he assures us, it will just have to wait a little longer to be realised.