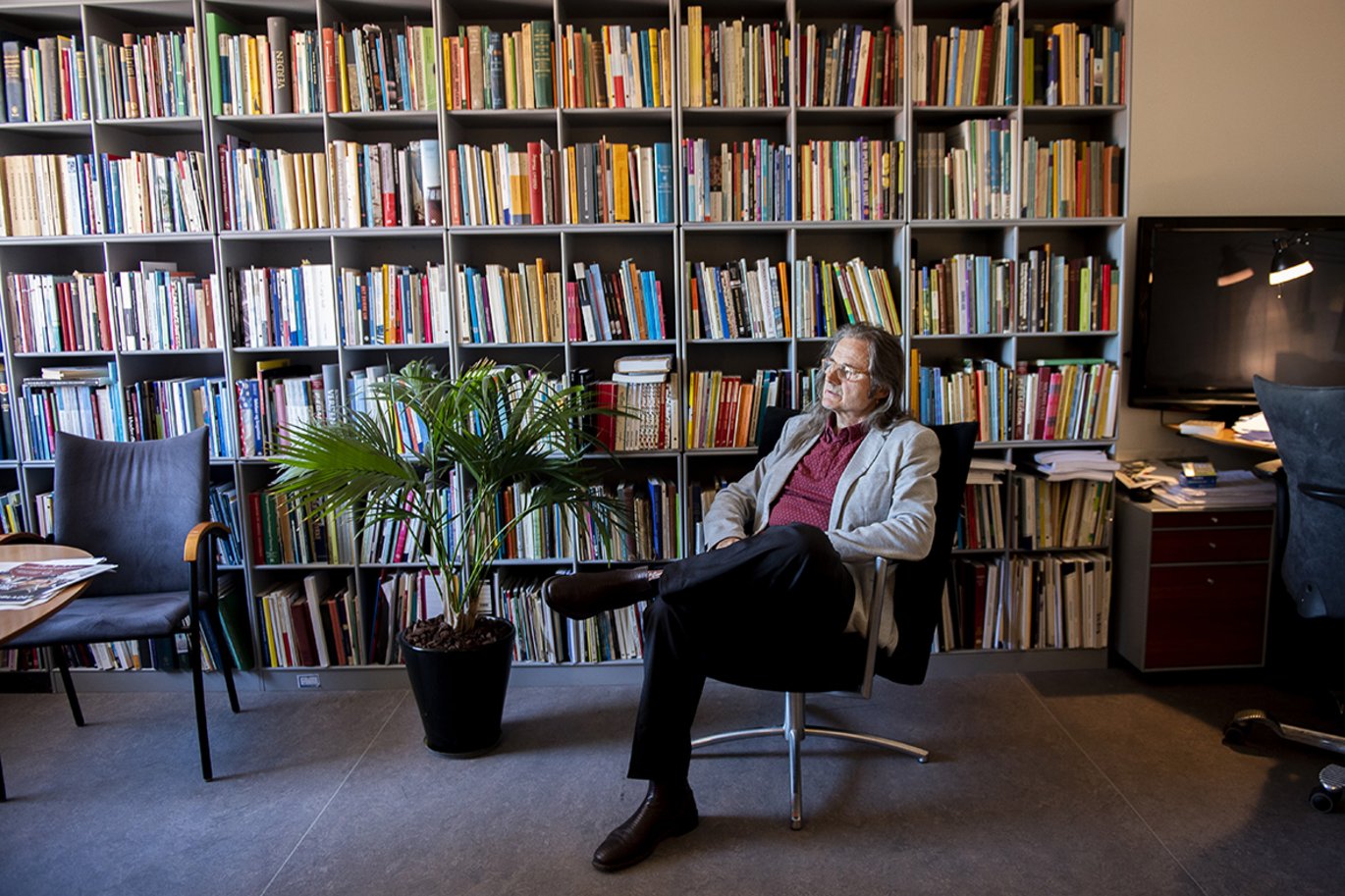

Show me your office – Lars-Henrik Schmidt

At the Danish School of Education in Emdrup, a counter-clockwise man sits in a tower philosophizing about clockwise coiled creatures. About the load-bearing structures of human and other living beings. Historian of ideas and philosopher Lars-Henrik Schmidt has been thinking deep thoughts up there in his tower for the past four decades – and even though he does come down from time to time, he’ll be celebrating his 40th anniversary on September 7th this year.

“I myself drink cider, but I believe I have some water in the storeroom,” says Lars-Henrik Schmidt, as he disappears through a door in his office that’s so low he has to duck quite a lot to keep from hitting his head on the doorframe.

There’s a white wooden sign that says ‘Director’ in elegant black lettering on the little door that leads to the room Schmidt refers to as a storeroom.

When he pops out again, he explains that he brought the sign with him when he moved into his current office in the tower on the Danish School of Education (DPU) campus in Emdrup.

Schmidt, who has a degree in the history of ideas and philosophy from Aarhus University, was director of the then Danish Institute for Education from 1996 to 2000, and subsequently rector of DPU from 2000 to 2007, when DPU merged with Aarhus University. He’s also been a member of the Danish Council of Ethics for a number of years.

Schmidt, who has a degree in the history of ideas and philosophy from Aarhus University, was director of the then Danish Institute for Education from 1996 to 2000, and subsequently rector of DPU from 2000 to 2007, when DPU merged with Aarhus University. He’s also been a member of the Danish Council of Ethics for a number of years.

But first and foremost, Schmidt is an abstract thinker, and he’s comfortable viewing our existence from above. But don’t let that fool you: Lars-Henrik Schmidt grew up in poverty in a not particularly loving family in a working-class neighbourhood in Vejle, a provincial town in east Jutland.

What made you decide to study the history of ideas?

“I had always known that I wanted to do something in that direction, even though I don’t come from a cultivated background. I’ve always been a bookworm, and I’ve also always been good at thinking in systems, in -isms.”

However, Schmidt father was strongly against his choice of subject:

“He wanted me to study law. Not because he was interested in law. But because then nobody would be able to screw us over,” Schmidt comments wryly.

Nonetheless he decided to study the history of ideas, even though his career prospects were dim, and afterwards, he intended to study medicine. Yes, he was interested in medicine – but he was primarily motivated by a need to provide for himself. But his story took a different turn – and Schmidt has succeeded in providing for himself and his family nonetheless. To the tune of a detached house with a garden in the fashionable (and extremely expensive) Frederiksberg quarter in Copenhagen.

What object in your office says most about you as a person?

“I have it right here in my pocket,” Schmidt says without hesitation. He places a small figure on the table.

“A beautiful woman who symbolises beauty, learning and hard work I got on a study trip to Vietnam. Not many people know this, but a large proportion of the Vietnamese liberation army were women. It’s a banal object, but she symbolises enthusiasm. She wills something, and she wills it together with others. And taking up the battle against oppression, that’s not banal.”

Spoken like a historian of ideas. But also like a boy from a working-class neighbourhood. Who in fact was born on Karl Marx Plads in Vejle.

“I’ve never been a member of a party. But I’ve always known that the class struggle exists. Saw throughout my childhood and youth how more and more families fought their way out of ‘the hole’ where we lived up into the air in the hills around Vejle. Up there where even the weather was better,” Schmidt laughs.

He continues in a quieter tone:

“I have a a little trouble seeing what the young are fighting for today.”

Do you mean the students?

“Yes, and my own children,” says Schmidt, whose gaze returns to the little Vietnamese figurine.

“I often have it in my pocket, and it’s gone from being just an object to taking on a form, a meaning. And that’s linked to the fact that I now have grandchildren. I touch it, thinking: ‘My time is over, but the next generation will find their world.’”

Briefly, there’s silence in the office. But only until I ask Schmidt a question that sets him off on a philosophical flight of fancy.

What item in your office says the most about you as a researcher?

“That would have to be this,” Schmidt says. In his outstretched palm, he holds the striped shell of a garden snail.

One of Schmidt’s preoccupations is what he calls the load-bearing structures of different forms of life. Like the snail, which carries its home on its back as it creeps its way through its snail existence.

“Se how strong it is (as a structure, ed.),” Schmidt says, pinching the snail shell between his fingers.

Strong? That’s not what I’ve experienced walking through my allotment in my clogs...

Schmidt looks at me with astonishment, which makes me wonder who’s actually overlooking something fundamental about existence, philosophers or the rest of us? He puts the snail shell down on a shelf, then stands a moment, apparently mulling over possible didactic strategies, before picking up a slightly larger spirally coiled specimen. There are plenty to choose from – molluscs are everywhere in Schmidt’s office. This one he presumably selects because allotments aren’t its natural habitat.

And then we’re launched – together with the molluscs – into the rarefied atmosphere of philosophical speculation.

And then we’re launched – together with the molluscs – into the rarefied atmosphere of philosophical speculation.

“I’m interested in understanding that there are other ways of bearing oneself than walking,” he explains:

“Snails and mussels bear their skeletons externally, and the question is whether it’s better to ‘build outside yourself’.”

Schmidt pauses, well aware that it’s difficult to follow him up to these heights of abstraction.

So he elaborates:

“I’m not searching for interiority! Because I’m afraid that we don’t have an inner core as human beings, or in any event I’m not sure that’s the case. The core that’s constantly referred to these days. That’s why I’m interested in skeletons. In the load-bearing structure. Of humans, of snails and of mussels. And of a building like Notre Dame.”

What drives Schmidt as a philosopher is the search for the banal, the simple and the elementary.

“What is simplicity in relation to bearing oneself? Is it smarter to be a snail? And if so, is that because the snail carries its house around? And doesn’t need legs like a human being – or buttresses like a building like Notre Dame?”

Schmidt explains that for him, it’s about seeing the familiar with new eyes.

“To be able to cast new perspectives on familiar forms. And here what’s most important to me is the ability to shift perspective.”

He continues:

“It’s not always clear, what historians of ideas say.”

But that’s ok, because as he also says:

“The path to clarity, that’s what philosophy is.”