Show me your office - Brian Bech Nielsen

On 1 September 1977, a hopeful young man from Holstebro began his degree programme at the Department of Physics at AU. Today, forty years later, he is still here. In the rector’s office on Nordre Ringgade in Aarhus.

The fact that four decades have passed since Rector Brian Bech Nielsen went to his first lecture is not the only red-letter day in his calendar this week. On Sunday he turns 60. Not that it bothers him. And then again. But we can come back to that when the time is ripe. Which is to say, after being allowed to pry in his office a little.

What items in your office say most about you as rector?

"As I see my task as being to safeguard the university, it must be a photo of a front page from Aarhus Stiftstidende (the local newspaper, ed.) from 11 September 1933 of Aarhus University's main building being inaugurated. The university builds on a tradition, and that tradition is very beautifully described in the article. By the way, it’s also entertaining to read because of the pompous language of that time."

What do you have to safeguard?

"The university plays an extremely important role for society as a whole and for its development. I’m not just talking about natural science, which is where I come from. I’m also talking about ideas, debates, culture in general. These are some of the areas in which we deliver something to society. An institution of such importance for society and its development is worth safeguarding."

If you safeguard something, you are also protecting it. Where do you see it as your job to do that today?

"The university is now stronger than ever before. It’s also bigger and it thus interacts much more with society than previously. So there is certainly no crisis if you look at it in a historical perspective.

"But it's still clear that there are some contemporary trends that are cause for concern. Fake news, alternative facts. The respect for knowledge that was there when I was younger isn’t as pronounced today. This means that as we build on knowledge, we have an even bigger task, which is to make sure – and yes, to safeguard – knowledge and ensure that it is used in a serious manner and not in a distorted form."

Fake news has also become a buzzword. What do you think it means?

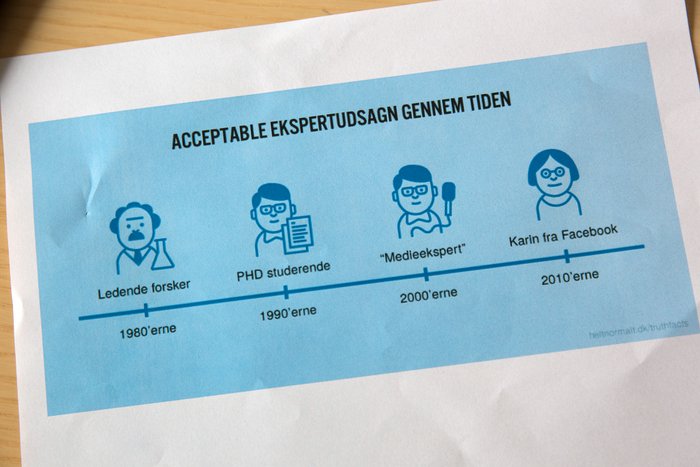

The rector reaches for an A4 sheet with the heading “Acceptable expert statements over time."

"In the 1980s the expert was a senior researcher, in the 1990s a PhD student, in the 00s, which is where the need for more and more news turns up, the journalist asks other journalists, and today it is Karin from Facebook."

The rector puts the paper back in the bookcase behind his desk.

"There’s a shred of truth in it. Of course, it’s important that everyone gets a chance to speak. That’s part of the democratic debate. But you have to be careful not to give all statements equal status. There must be an inherent respect for the fact that someone has actually looked into things and speaks with greater weight than others. That’s the area where we’re challenged at the moment."

What items here in your office say most about you as a person?

The rector walks over to a picture in a golden frame, which he got from his "dearest wife" when he became rector.

"I'm generally interested in many topics, but I have two very particular interests. One is physics and the other is history. I love both. The pleasure of knowing something. It’s an integrated part of me, as it is for virtually all university people. I love that I know that this historical picture shows the Skirmish of Aarhus and that it took place on 31 May 1849. That’s the kind of thing I can feel pleasure about knowing."

One corner of the rector’s mouth smiles a little as he continues:

"It's actually also a really good picture of the university. It's not really an organised flock. They run around in all directions. Sometimes there is a bit of a commotion. You can also wonder if it’s the one on the horse who is rector, or whether it’s him over there," says the rector and points to a man who has lost his horse, which must be a little uncomfortable in the middle of a life or death skirmish.

Which do you think it is?

"I want to be the one on horseback. But aren't there situations where all of us are the other person?" asks the rector and points again to the man running around on foot in the middle of the battle.

Just now you talked about the pleasure of knowing something. Where does that pleasure come from?

"My childhood. I come from a family where there was focus on it being good to know things. But it also comes from the teachers in the school system. I’ve got really good memories of several of my school teachers and, not least, teachers in upper secondary school, which was deeply inspiring. I love knowing something, being able to name all the countries in Africa and sketch where they are. That kind of thing. I think putting things into context is wonderful."

Why is it important?

"I think it’s been useful. I think that’s what I’d say, instead of calling it important. For example, if I sit together with almost any ambassador, it’s a pleasure to know a little about the country that person comes from and its history. That means that the barrier for getting into a conversation has already been lowered considerably."

Another item in the office that the rector thinks says something about him as a person is a special golden hat with a propeller on it.

He received it from TÅGEKAMMERET, which is a student association at the faculty of science and technology. An association that the rector himself was once a member of.

"It was great that the students thought it worthwhile celebrating my appointment as rector, and in some way, it also says something about managing not to completely lose touch. It’s also a reminder of why we’re here. The students are what it’s all about."

What books do you have in your office?

"Some of them are books I’ve been given as rector. Books that our own people have contributed to and which I would like to read. I also try to read them, but there isn’t much time for it. But the majority of the books are my textbooks. The one’s I had on the shelves of my office as a physicist. I come from the generation that grew up with books, so even though I read a lot on the computer, there is a special feeling when you have one of your old books in the palm of your hand."

"And, in a way, having them here also brings me into contact to my subject. I have used several of the books for lecturing, and you always have a special relationship with them when you’ve been deeply interested in the subject. I also have them as a reminder. I think it’s important to remember where you come from in the organisation."

He notices that the photographer has pointed his camera at a vase standing on a shelf below the picture of the Skirmish of Aarhus in 1849.

"There’s actually a nice little story about that. When our former chairman of the board Michael Christiansen left, I wanted to give him a personal gift. On the internet, I found a vase in royal porcelain that depicted Aarhus University. See, it’s with the old main building," says the rector, pointing towards the middle of the vase.

"It’s really old, made during the war. So I thought: I’ll give that to Michael."

Very happy with himself, Bech Nielsen showed the vase to his wife when he came home with his package.

"She disappeared behind the kitchen table, and when she reappeared it was with a sound that I know means that something isn’t quite right. And then she said: What you’ve got there is present for someone you don’t like very much! It’ll end up on the bottom shelf in a holiday cottage far from Aarhus," laughs the rector.

"Then I'll keep it for myself, I answered. And when I eventually retire, I intend to donate it to the university historians, who can look after it for ever!"

What did you end up giving to Michael Christiansen?

"A small coin representing a royal succession. I also told him the story of the vase, and when I showed it to him, he seemed very happy with the coin."

"Come on! That ain’t even bullshit. That’s horseshit!"

Bech Nielsen presses a big red button standing on his desk and that’s what you hear.

"It has four variations, but my favourite is this one:

"Bullshit detected! Take precautions!"

"I got it from one of our professors, and I've taken it to one senior management team meeting. It was quite entertaining, in fact so entertaining that I decided I’d better not take it along next time."

Next to the button is a small rubber stamp with its own stamp pad.

"I got that from the same professor. But I don’t use it, though I must admit that I often feel like it. But if you’re smart, you don’t do that."

Smart from experience, for example.

"Once I wanted to just try it out, and I also stamped a piece of paper, but the dean came in at the very same moment that I handed over the paper. He did a double take," laughs the rector.

From his desk, the rector has a view of the square next to Stakladen and Studenterhus Aarhus. A view he appreciates for several reasons.

"The square can initially seem a little cold. I would have preferred a little more greenery like a tree in the middle. But there is actually a lot of life. For example the skateboarders who practice there.

"But what I like best is when the students sit there in the good weather. Studenterhus Aarhus in particular has many international students who often sit outside and enjoy themselves. When I have the window open, I can hear them. Being able to get a sense of all that life is great. But even though the square is used, it’s rarely full. As a rule, that only happens if there is a demonstration."

The rector turns 60 on Sunday 3 September. He is not at all bothered by his own birthdays, but this time around it has led him to think about a few things.

"I can feel that it makes a bit of an impression. When I turned fifty, the thought passed through my head that the next big birthday would be my sixtieth. But now the next big one is seventy, and then I’ll have certainly reached the point where my working life is at an end. That’s the latest I expect to retire."

"After all, it’s just as big an upheaval as beginning at university was. In a way I’ve thought: Well, there’s only ten years anyhow and ten years pass quickly. I think everyone has a sense of time passing faster as they grow older. Some feel sad about it. But on the other hand, it’s also a sign that we’re very good at filling up our calendars. As a physicist, I can say one thing with certainty: Time does not pass faster."

Translated by Peter Lambourne