Show me your office – Steffen Krogh

Steffen Krogh, associate professor of Germanic linguistics, reads a lot of his books backwards – from right to left – and is a frequent guest in ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities which normally shun outsiders. Steffen is one of the world’s leading authorities on Yiddish, the historical language of the Ashkenazi Jews, and speaks it fluently.

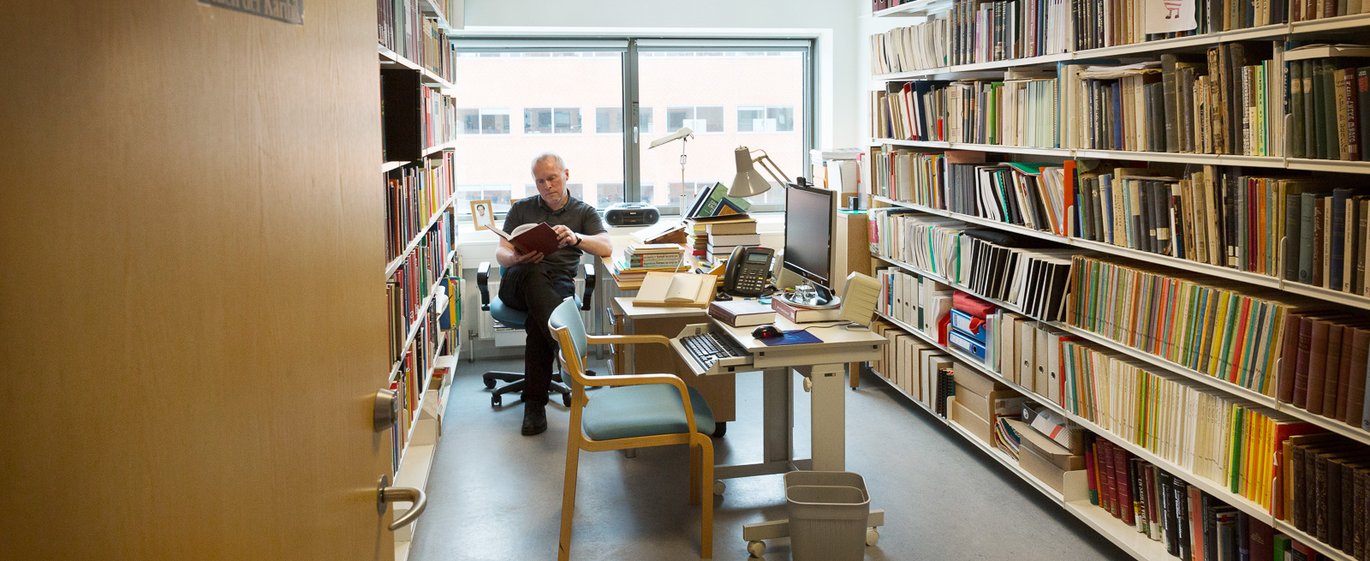

A librarian would feel right at home in Steffen Krogh’s office in the Nobel Park: the two longest walls of the rectangular office are covered in books from floor to ceiling. But the books can’t be borrowed, Steffen stresses. And in any case, few people would get much out of them, because a lot of them are in Yiddish.

Steffen has been an associate professor of German and Germanic linguistics since 1995. He teaches six hours a week and supervises students – and does research on Yiddish.

What’s on your desk right now?

“I’m working on a couple of publications – one is an English publication about Yiddish in the United States. The other one’s about Low German influence on Danish in the Middle Ages. That’s why Håndbog i Nedertysk [Low German handbook] is here. And I also need to prepare my 2pm class.”

Steffen has two lecterns on his desk and a book stand holding the books he’s currently using.

“My father made them. He was a schoolteacher and skilled at making things like that. The lecterns keep my back from hurting when I sit and read.”

There’s also a green coffee mug on the desk – one of Steffen’s most prized possessions.

“I bought it in New York in 1999 when I was doing research at Columbia University. I was living in a five-room apartment in Manhattan I’d borrowed from a professor who wasn’t using it and who was willing to lend it to me.”

So anyone who accidentally takes your mug out of the dishwasher from the break room had better watch out?

“It never goes in the dishwasher. I wash it by hand and take it back to my office.”

Why did you end up choosing Yiddish as your research field?

“I wanted a little more life in my research, because I’d been working on dead languages a lot, like Gothic, which disappeared 1,000 years ago. So I got interested in Yiddish. A language which was also close to extinction. This was the language that the Jews spoke in the concentration camps, but fortunately there were enough survivors so that their language survived as well,” Steffen explains.

“It sounds like German, but it’s written in Hebraic characters, so you have to be prepared to learn a lot of languages if you’re going to work on Yiddish. I’ve always been interested in learning languages and in exploring how contact relationships between them work.”

In addition to Danish, his mother tongue, Steffen speaks German, Yiddish and English in that order. And although he’s not fluent, he also has a working knowledge of 15-20 other languages: including French, Russian, Slovak, Hungarian and a variety of ancient languages, including Greek, Latin and Hebrew.

What would you save if your office was burning?

“I would try to save my Yiddish collection, which I had shipped home in crates. I would also take my collection of ultra-Orthodox newspapers, and three [Yiddish] grammars from Eastern Europe, which are pre- WWII and really rare.”

Steffen opens a small cabinet right inside the door.

“And I’d also make sure I took this with me,” he says, pulling out a thick old tome.

“It’s from 1616, and it was written by my 9 x great-great grandfather Thøger Mortensen Hvass, who was a rural dean in Viborg. It’s a devotional work, 600 pages long, without page numbers or chapters. Unfortunately, this is not my copy – I borrowed it from the State and University Library.”

“Finally, I would save these photos of my two sons, Jacob who’s 12 and Kristian who’s 17. By the way, they made the papier-mäché troll in the corner and those drawings.”

Steffen explains why he finds the study of Yiddish so fascinating as a linguist.

“It’s a relatively unexplored area, so there’s lots of pioneering work to be done. This is completely impossible for German, which is a very thoroughly described language.”

One pioneering project Steffen has launched is a description of word order in Eastern European Yiddish.

“No one had done any professional work in that field when I started. And I’ve done a lot of work on Yiddish as it’s spoken among ultra-Orthodox Jews, primarily in the United States, Israel, Great Britain and Antwerp in Belgium.”

Can you give us an idea of your status in the field of Yiddish studies?

“Umm, that’s not a good question to ask someone from Northern Jutland. But I am one of the few researchers in the world with documented experience with ultra-Orthodox Yiddish. There’s not a publication on ultra-Orthodox Yiddish or a conference on the subject that I don’t contribute to.”

Some people might think that Yiddish is kind of a niche subject?

“In relation to German, it might seem like a niche, but it’s a large language community, and research on Yiddish makes a valuable contribution to the more general science of linguistics. I once met a researcher who worked on the retina as a metaphor in French film. Now that’s niche.”

And how do you go about doing research on a language like Yiddish? As you would imagine, part of the job involves travelling to Jewish communities, where Steffen interviews people, for example if someone speaks a particular dialect. One of these subjects is the pretty woman in the photo below.

“This is an older – now probably deceased – woman from Rumania. If she’s alive, she’s 98 years old. The Yiddish spoken by the elderly in that region is the precursor of ultra-Orthodox Yiddish. She invited me home so I could interview her. And that’s where I saw this picture of her as a young woman. She was very beautiful, so I asked if I could have it. She was a little dubious: ‘What do you think your wife will say to that?’ But she let me have it.”

And what did your wife say?

“Nothing.”

Behind the door – and Steffen stresses that this is not some kind of naughty corner – is another older photo.

“That’s my great idol, the linguist Uriel Weinreich. He came from Vilnius and is one of the greatest scholars of Yiddish who ever lived. I was given that photo by his widow because I told her that I wanted a picture of her husband, whom I consider an important and brilliant linguist. So she had this made for me. And because the door to my office is often closed, I have a fine view of it from my desk.”

Steffen’s office hours are posted outside his door, along with a quote from the German writer Martin Walser: Irritating people arrive unannounced. They are evil. But those one longs for do not come. Next to this hangs a postcard from the Jewish deli Zaftig’s Delicatessen in Boston.

Translated by Lenore Messick